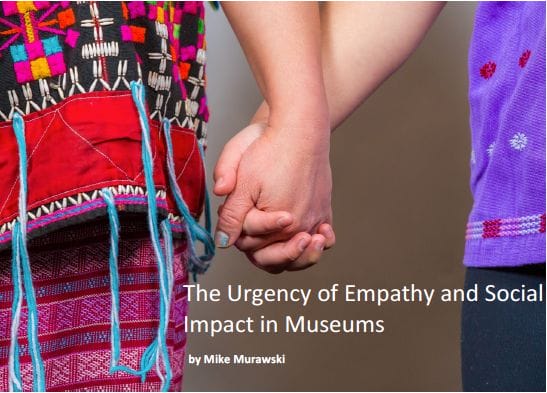

About the photo: Recent refugees from Burma/Myanmar, Paw Saw and Kue Mah Wah clasp hands as they tell their story. Object Stories, Portland Art Museum. Photo by Cody Maxwell.

“We are in more urgent need of empathy than ever before.” 1

This quote has repeatedly been on my mind over the past weeks, months, and sadly, years — as senseless acts of violence and hatred hit the headlines at a numbing pace of regularity. I began writing this article at the end of the first week of July 2016, when the country was reeling from the deaths of Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, and five police officers in Dallas—Lorne Ahrens, Michael Krol, Michael J. Smith, Brent Thompson, and Patrick Zamarripa. So many of us were still processing the horrific attack at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando less than a month earlier, while simultaneously witnessing an alarming spike in hate crimes and xenophobia in the U.K. immediately following the Brexit vote. This all corresponded in unsettling ways to the divisive rhetoric and acrimonious tone of the presidential campaign here in the U.S.

In moments like these it is important for museums — and the people who work for them — to pause and reflect on the roles that we serve within our communities. Yes, museums are institutions that hold collections. But they can also serve a powerful role with our communities as active spaces for connection and coming together, for conversation and dialogue, for listening and sharing. Museums can be spaces for individual stories and community voices. They can be a space for acknowledging and reflecting on differences, and for bridging divides. They can be spaces for growth, struggle, love, and hope.

The words I open with come from Roman Krznaric, author of Empathy: Why It Matters, and How to Get It (2014a) and founder of the Empathy Library. Krznaric is among a growing chorus of voices who see an urgent need for empathy and human understanding in an era too often marked by violence, hatred, resentment, self-interest, and toxic political and social debates. In his 2014 TEDx Talk “How to Start an Empathy Revolution,” he defines empathy as “the art of stepping into the shoes of another person and looking at the world from their perspective. It’s about understanding the thoughts, the feelings, the ideas and experiences that make up their view of the world” (Krznaric 2014b).

In September 2015, Krznaric put these ideas into practice in the realm of museums with the development of the Empathy Museum, dedicated to helping visitors develop the skill of putting themselves in others’ shoes. Its first exhibit, A Mile in My Shoes, did quite literally that, setting up in a shoe shop where visitors are fitted with the shoes of another person, invited to walk a mile along the riverside while being immersed in an audio narrative of this stranger’s life, and then write a short story about it. With contributions ranging from a sewer worker to a sex worker, the stories covered different aspects of life, from loss and grief to hope and love.

In September 2015, Krznaric put these ideas into practice in the realm of museums with the development of the Empathy Museum, dedicated to helping visitors develop the skill of putting themselves in others’ shoes. Its first exhibit, A Mile in My Shoes, did quite literally that, setting up in a shoe shop where visitors are fitted with the shoes of another person, invited to walk a mile along the riverside while being immersed in an audio narrative of this stranger’s life, and then write a short story about it. With contributions ranging from a sewer worker to a sex worker, the stories covered different aspects of life, from loss and grief to hope and love.

Developing empathy has the potential to create radical social change, “a revolution of human relationships,” Krznaric states (2014c). So how can we spark this empathy revolution in museums?

Museums Are Us, Not It

I want to start by making an important foundational point about how we talk about museums. When we talk about them only as brick-and-mortar institutions or as “it,” it becomes easier to distance ourselves from the human-centered work that we do. So it’s absolutely essential to remember that museums are made of people: from directors, board members, patrons, and curators to educators, guest services staff, registrars, conservators, security guards, volunteers, maintenance and facilities workers, members, and visitors. I am reminded of this by the Director of Learning at the Tate Museum, Anna Cutler, whose memorable 2013 Tate Paper discussed institutional critique and cultural learning in museums. In it, she quotes artist Andrea Fraser: “Every time we speak of the ‘institution’ as other than ‘us’ we disavow our role in the creation and perpetuation of its conditions” (Cutler 2013).

I want to start by making an important foundational point about how we talk about museums. When we talk about them only as brick-and-mortar institutions or as “it,” it becomes easier to distance ourselves from the human-centered work that we do. So it’s absolutely essential to remember that museums are made of people: from directors, board members, patrons, and curators to educators, guest services staff, registrars, conservators, security guards, volunteers, maintenance and facilities workers, members, and visitors. I am reminded of this by the Director of Learning at the Tate Museum, Anna Cutler, whose memorable 2013 Tate Paper discussed institutional critique and cultural learning in museums. In it, she quotes artist Andrea Fraser: “Every time we speak of the ‘institution’ as other than ‘us’ we disavow our role in the creation and perpetuation of its conditions” (Cutler 2013).

This is an important basis for any discussion of empathy and museums, since it defines the vision, mission, and work of a museum as the vision, mission, and work of the people who belong to that museum. So if we, myself included, say “museums must be more connected to their communities,” we’re really talking about what the people who make up the museum need to focus on — being more connected to our communities. We are inseparable from the institution, in other words. Any critique of museums is a critique of us; and any change needing to happen in museums is, therefore, a change that needs to start with us.

The Growing Role of Empathy in Museum Practice

Krznaric’s work with the Empathy Museum is but one small example of the types of civically engaged, human-centered practices that have been instituted in an effort to expand the role that museums serve in building empathy and human connection in our communities. Staff working for museums across the globe are launching new efforts to bring people together, facilitate open dialogue, and elevate the voices and stories of marginalized groups to promote greater understanding.

For example, I continue to be amazed and inspired by the Multaqa Project developed in 2015 by Berlin’s state museums, which brings in a group of refugees from Iraq and Syria to serve as Arabic-speaking guides.2 The project title, Multaqa, means “meeting point” in Arabic. The tours are designed to give refugees and newcomers access to the city’s museums and facilitate the interchange of diverse cultural and historical experiences. The tours have been so popular, according to a recent report, that the organizers are looking to expand the program to include “intercultural workshops, which the Berlin public can also participate in” (Neo 2016).

The Canadian Museum for Human Rights, an inspiring institution in so many ways, currently houses six different exhibits that explore the tragic story and legacy of the Indian Residential School System, one of Canada’s most pressing human rights concerns. As a national museum and hub of human rights education, the Museum has an important role to play in efforts toward reconciliation between indigenous and non-indigenous people in Canada. As is stated in the summary report of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission: “Through their exhibits, education outreach, and research programs, all museums are well positioned to contribute to education for reconciliation” (2015). The team at the Canadian Museum of Human Rights is also working to keep the conversation alive and involve the voices of its communities, especially through its Share Your Story Project that allows anyone to record their own story about human rights or listen to the individual experiences of others.

In their book Cities, Museums, and Soft Power, Gail Dexter Lord and Ngaire Blankenship discuss the human social behaviors of bridging and bonding that museums have the distinct potential to promote and amplify, especially through public programs, education, and exhibitions. Their final essay offers a comprehensive set of strategies for how museums can be of greater value to their cities and communities:

Museums and cities have a strong role to play together in bridging and bonding. They bring people together at similar life stages … or with identity in common … where they can share their experiences. Museums also bridge among identities, offering a public place to bring different groups together around similar interests. (p. 222)

Also featured in this issue of the Journal of Folklore and Education, the International Museum of Folk Art’s Gallery of Conscience, inaugurated in 2010, serves as truly unique and visionary example of how museums are experimenting in this area. The Gallery’s goal is to be an agent of positive social change by engaging history, dialogue, and personal reflection around issues of social justice and human rights. Since inception, exhibitions have explored how traditional artists come together in the face of change or disaster to provide comfort, counsel, prayer, and hope through their art. This focus has earned the space membership in the International Coalition of the Sites of Conscience.

Building a Broader Culture of Advocacy

The type of museum practice I’ve highlighted is certainly not new. Many of us read about this work in museum blogs (such as Incluseum, Thinking About Museums, Visitors of Color, Queering the Museum, Brown Girls Museum Blog, etc.) and emails from the Center for the Future of Museums. Many of us work on programs like these ourselves. But what concerns me is that across much of this practice, I find a lack of a broader institutional culture of support. Too many community-based projects like those above end up being relegated to education staff, isolated from the core mission of an institution, or left entirely invisible. And this lack of supports extends beyond the walls of the museum. When journalists, scholars, and critics write about museums and exhibitions, they frequently ignore or denigrate the spaces that invite visitor engagement and community participation. There are even individuals in my own field of museum education who refer to empathy-building practices and affective learning strategies as too “touchy feely.”

We museum people need to work together to build a stronger, collective culture of support and advocacy for museum practice based in empathy, inclusion, and social impact. This is some of the most meaningful, relevant work in museums right now. People across our institutions — not just educators but directors, curators, marketing staff, board members, donors, etc. — need to be publicly and visibly proud of the programs, exhibitions, and projects that actively embrace individual stories, dialogue about provocative questions, and the diverse and rich lived experiences of those living in our communities. More comprehensive support for this work can lead to an expanded focus on social impact and community engagement in a museum’s strategic goals and mission, in its exhibition and program planning process, and in its allocation of resources.

So let’s all be prouder of the work we’re doing in museums to bring people together and learn more about ourselves and each other — from tiny one-off gatherings and events to much larger sustained initiatives.

Time for an Empathy Revolution in Museums

How do we start an empathy revolution in museums? How do we more fiercely recognize and support the meaningful work that museum professionals are already leading to support open dialogues around the challenging, relevant issues of our time? And how do we radically expand this work to build a stronger culture of empathy within museums — one that measures future success through our capacity to bring people together, respond to local realities, foster conversations, and contribute to strong and resilient communities?

In 2013, the Museums Association of the U.K. launched its Museums Change Lives campaign, establishing a set of principles based on research, conferences sessions, online forums, open public workshops, and discussions with charities and social enterprises.5 The core principles they developed from their vision for the social impact of museums are worth sharing to move this discussion forward and enact change:

- Every museum is different, but all can find ways of maximizing their social impact.

- Everyone has the right to meaningful participation in the life and work of museums.

- Audiences are creators as well as consumers of knowledge; their insights and expertise enrich and transform the museum experience for others.

- Active public participation changes museums for the better.

- Museums foster questioning, debate, and critical thinking.

- Good museums offer excellent experiences that meet public needs.

- Effective museums engage with contemporary issues.

- Social justice is at the heart of the impact of museums.

- Museums are not neutral spaces.

- Museums are rooted in places and contribute to local distinctiveness. (Museums Association 2013, p. 4)

These principles, as with much of their vision, are inspiring — but too often we stop there, feeling inspired but lacking action. The Museums Association report continues, “It’s time for your museum to respond to hard times by making a bigger difference. It’s time for you to play your part in helping museums change people’s lives” (p. 13). The report concludes with a set of ten actions that will help your museum improve its social impact. Here is a slightly abbreviated, edited list:

- Make a clear commitment to improve your museum’s social impact (i.e. having strategic goals).

- Reflect on your current impacts; listen to users and non-users; research local needs.

- Research what other museums are doing.

- Seek out and connect with suitable partners.

- Work with your partners as equals.

- Allocate resources.

- Innovate and be willing to take risks.

- Reflect on and celebrate your work. Learn from and with partners and participants.

- Find ways for partners and participants to have a deep impact on your museum. Bring more voices into interpretation and devolve power.

- Strive for long-term sustained change based on lasting relationships with partners and long-term engagement with participants.

Print these out, put them on your office wall, bring them to staff meetings, share these with your visitors and audiences, and have some open conversations about the “so what” of museums. Take these principles and action steps seriously. Build a broader team to advocate for the work you’re already doing at your institution; rethink existing programs; and bravely propose new projects and partnerships that better serve your community. See how a human-centered focus on empathy and social impact might change your own practice, your museum, and your community.

The best museums are now striving to realise their full potential for society and are far more than just buildings and collections. They have two-way relationships with communities…. They are becoming increasingly outward looking, building more relationships with partners. They are welcoming more people as active participants. (Museums Association 2013, p. 5)

Let’s be a part of making this happen!

Mike Murawski is founding editor of ArtMuseumTeaching.com and currently Director of Education and Public Programs at the Portland Art Museum. He earned his MA and PhD in Education from American University in Washington, DC, focusing his research on educational theory and interdisciplinary learning in the arts.

Endnotes

- Roman Krznaric quoted by Brigid Delaney in “Philosopher Roman Krznaric: ‘We Are in More Urgent Need of Empathy Than Ever Before.’” The Guardian, February 18, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/feb/19/empathy-expert-roman-krznaric-on-shifting-away-from-20th-century-individualism.

- For more information see “Multaqa: Museum as Meeting Point–Refugees as Guides in Berlin Museums,” http://www.smb.museum/en/museums-institutions/museum-fuer-islamische-kunst/collection-research/research-coopeation/multaka.html.

- For more information see http://portlandartmuseum.org/objectstories.

- See http://www.portlandmeetportland.org.

- See http://www.museumsassociation.org/museums-change-lives.

Works Cited

Blankenberg, Ngaire and Gail Dexter Lord. 2015. “Thirty-Two Ways for Museums to Activate Their Soft Power,” in Cities, Museums and Soft Power, ed. Gail Dexter Lord and Ngaire Blankenberg. Arlington: AAM Press.

Cutler, Anna. 2013. “Who Will Sing the Song? Learning Beyond Institutional Critique,” in Tate Papers, no.19, Spring, http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/19/who-will-sing-the-song-learning-beyond-institutional-critique.

Krznaric, Roman. 2014a. Empathy: Why It Matters, and How to Get It. New York: TarcherPerigee.

_________. 2014b. “How to Start an Empathy Revolution,” TEDxAthens 2013, video published January 2014,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RT5X6NIJR88.

_________. 2014c. “What Is Empathy,” in Empathy Library. Website. http://empathylibrary.com/what-is-empathy.

Museums Association. 2013. “Museums Change Lives: The MA’s Vision for the Impact of Museums,” July, http://www.museumsassociation.org/download?id=1001738.

Neo, Hui Min. “Refugees-as-guides a Hit at Berlin’s Museums,” in Star2.com. Website. May 18, 2016, http://www.star2.com/people/2016/05/18/refugees-as-guides-a-hit-at-berlin-museums.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015. “Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada,” http://nctr.ca/assets/reports/Final%20Reports/Executive_Summary_English_Web.pdf

This article was originally published July 2016 at ArtMuseumTeaching.com, which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.