Anonymous Dairy Farmer (Interviewee), Interview Excerpt – Vermont Dairy Farmer: “Luis could lasso a cow.” Folklife Primary Sources Repository, https://folksources.org/resources/items/show/29

Primary sources force us to complicate what we accept as the full story.

Alexandra S. Antohin, Journal of Folklore and Education Guest Editor

Primary sources allow us to think of documentation as beyond the reporting of information and repetition of established narratives and status quo thinking. They introduce the possibilities of comparison and contrast that highlight how events, memories, and values vary based on how they are experienced and by whom. They present the positive and negative sides of perspective. They can showcase bias, harmful representation, and partial facts. They also elevate testimonies, insights, and missing reflections. After all, how people make sense of the world is often personal. We are impacted most by what we can relate to. Primary sources force us to complicate what we accept as the full story.

Primary sources invite us to see knowledge as made up of many parts and pieces coming from different formats and directions. Ethnographic and folklife materials are especially good at this. These kinds of sources are mediated by the fieldworker whose identity and role in shaping the “collecting of material” is actively present. You can hear their voice on the audio recording, see them in the photos, read their handwriting in the artifact descriptions. Their presence shows us another truth about primary sources: The act of collecting is a form of individual selection and interpretation. Folklife and ethnographic collections are an invitation to continue to contribute to the evolving representation of everyday life.

These kinds of sources matter because they make the case that we all have a role to play, not only as interpreters of historical and contemporary details as they are passed down but also as key contributors in how these details are carried forward.

Booker, Kenny (interviewee); Alexander, John (interviewee), Interview Excerpt – “What started this riot.” Folklife Primary Sources Repository, https://folksources.org/resources/items/show/59

Primary source materials matter because they help us understand who we are as people.

Sarah Milligan, Oklahoma State University Library, Oklahoma Oral History Research Program

Primary source materials matter because they help us understand who we are as people. We can get a glimpse into the perspectives and actions of individuals around us, whether decades before we were born or existing alongside us, which can help us understand ourselves today. Especially looking at ethnographic primary sources, we can experience direct conversations related to how traditions, communities, families, etc. have carried forward and changed over time to contextualize what we experience today.

Broad representation for perspectives in primary sources is essential to share an egalitarian history of a people sharing space over time.

Burns, Joe (interviewee); Clark, O.G. (interviewee); Jackson, Mrs. G.E. (interviewee), Interview Excerpt – “Were you aware of what started this riot?” Folklife Primary Sources Repository, https://folksources.org/resources/items/show/60

Primary sources matter because points of view and perspective-taking matter.

Shanedra D. Nowell, Oklahoma State University, School of Teaching, Learning, and Educational Sciences

Primary sources invite us into the lives and experiences of people who lived long ago and to those who live today just down the street. They allow us to see the world through someone else’s eyes and to take in different perspectives. As a history teacher, I often teach students that primary sources are first-person accounts of the events we are studying. Reading the personal diary of a woman eking out a living alone on the prairie or sorrowful, yet hope-filled words of a Holocaust victim, these voices give students a way into the past that is not possible with secondary and other sources. As we teach students to think and write like historians, it is important for them to realize we are living through history. They are creating primary sources everyday with their tweets, snaps, reels, and poses on the gram, which may be collected and cataloged to create tomorrow’s history. Their thoughts and perspectives matter as much as those we read, view, and analyze to understand eras of the past.

Primary sources matter because points of views and perspective-taking matter. We need to see and understand the world through others’ eyes, lives, and experiences to understand better who we are, how we got here, and where we are going. These experiences that focus upon point of view help us learn to talk to each other and to work together to create the world we want to see.

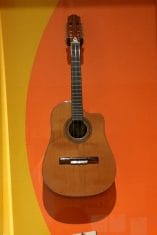

Rojas, Leandro (maker). Artifact: Tres Guitar., Folklife Primary Sources Repository, https://folksources.org/resources/items/show/45

Primary sources allow us to be curious and may inspire more questions than answers.

Vanessa Navarro Maza, HistoryMiami Museum

A primary source is an opportunity for connection and a window into the life of a person or group of people. Primary sources allow us to be curious and may inspire more questions than answers.

Most of recorded history deals in the triumphs and challenges of world leaders, royalty, the rich, and the powerful. Primary sources help us not only to understand these public figures better as human beings, but also to get a sense of what life was/is like for everyday people living in a specific place and time. First-person narratives, whether written stories or recorded interviews, are records of self-expression and contemplation that help us connect on a deeper level with the human experience. Photographs capture a moment in time and allow us to connect visually with the environments or activities of others, whether they are a neighbor or someone who lived hundreds of years ago. Objects are tangible remnants of a person’s time on earth that can connect us physically to their talents, traditions, values, and so much more.

In engaging with primary sources, it is important to think critically about how we are all actively involved in the creation and interpretation of these sources. They are alive and flexible. The processes through which they are documented, categorized, made accessible, and interpreted are carried about through human interaction. Personal biases and experiences inform these interactions. Some questions to consider when engaging with a primary source are: What are some of the layers of interpretation that are contributing to your engagement with that source? What are the descriptions or keywords that are attached to this source that may influence the experience of what you’re seeing, hearing, or touching? Could this be described or categorized in a different way? How can bias play a role in assigning these descriptions or categories?

Primary sources also bring up important questions about how much agency people have in the collecting, displaying, and interpretation of a source of or about them, whether it is an object they made, an interview they gave, or a photograph of them. As folklorists, ethnographers, and museum curators, we make choices about whom to invite into our spaces, what objects to collect, whom to interview, and what to photograph or document. When engaging with a primary source, you may ask yourself: How much agency did this individual or group of people have in representing themselves? What are some of the choices they may or may not have been able to make during this process of documentation, categorization, and presentation? How could we find out more about what this person or group of people found valuable and important about this primary source? Does that information matter?

Collins, Marjory (photographer). New York, NY. Chinese American girl playing hopscotch with American friends outside her home in Flatbush. United States, New York, New York State, 1942. Photograph, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017835800

Primary sources offer access to diverse perspectives on topics that have significance for the hyper-local, yet can extend to deep global and historical connections.

Lisa Rathje, Executive Director, Local Learning: The National Network for Folk Arts in Education

Primary sources that come from ethnography and cultural documentation offer access to diverse perspectives on topics that have significance for the hyper-local, yet can extend to deep global and historical connections. Primary sources can spark curiosity and offer opportunities for inquiry. They can teach us new narratives about a time, a place, or an event. Primary sources can also complicate a story.

The process of ethnography and documentation provides tools for ethical collaboration and connection within communities. The products of this process matter because they are texts that are necessary for deeper understanding of ourselves, our many communities, and our multiple histories. Also, this is not just about the record for people who did not experience that event, that place, or that time. Primary sources save things for the community. People may have access to their own story that otherwise is lost or not amplified through formal education or dominant narratives. Youth pay attention to what is valued by society, and seeing a record of their community stories as texts that should be taught matters.

Teaching with primary sources matters because the critical analysis of these texts offers opportunities to consider significant topics in Social Studies, Literacy, and Civics, such as subject position, multiple truths, the complexity of memory, and the ways we need ALL of these diverse and sometimes contradictory stories to understand where we have been to better chart our future.

Now we ask: What does a primary source mean to you?

Now we ask: What does a primary source mean to you?

Noticing that primary sources come in many formats and from across time and place begins to suggest the many ways primary sources can be useful in teaching and learning. To see more from this team of authors and the Local Learning Teaching with Folk Sources Project, explore Issue 2 of this Volume of the Journal of Folklore and Education.

Content created and featured in partnership with the Teaching with Primary Sources program does not indicate an endorsement by the Library of Congress.