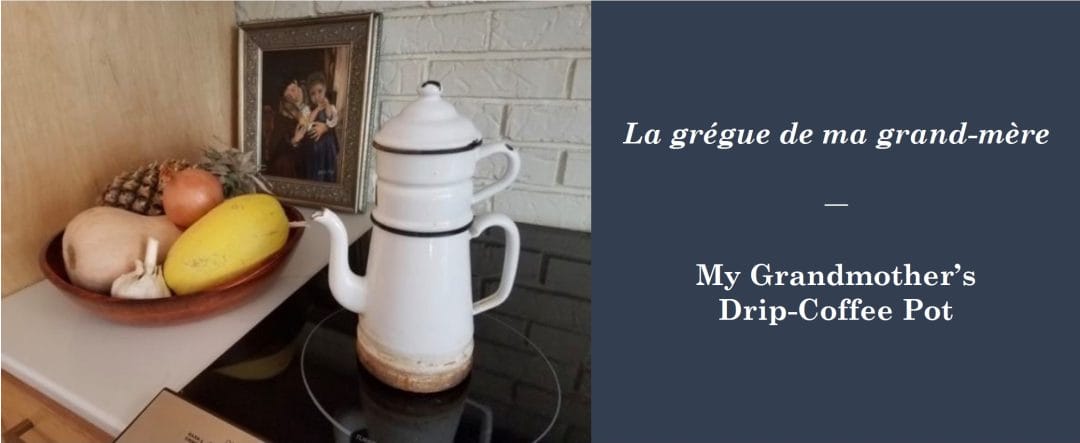

Mid-last-century, before Interstate 10 sliced through swampy basins and bayou-lined prairies in Louisiana to tether California to Florida, French was already beginning to fade as the vernacular in our rural, post-WWII community. However, my family still drew upon its Acadian and European French roots linguistically and upheld cultural traditions surrounding family, Catholicism, and land. French was my father’s first language. Even in our English-speaking household, conversations were salted and peppered with French. When Daddy wanted to visit friends in the evening, he proposed making a little veillée. Any random desire was expressed as an envie. We never asked for French toast, but we did enjoy pain perdu for breakfast while my grandparents made their coffee in a grégue. I heard French spoken among family, in church, between my dad and his hunting buddies or friends from his youth, and on television. Each Saturday afternoon before the Lawrence Welk Show aired, our local CBS affiliate featured music by a venerable Cajun accordionist and his band who performed waltzes and two-steps sung in French.

Our seasonal round of traditions included partaking in harvest festivals that promoted agricultural products and contests in towns all around Louisiana’s Acadiana region. For example, my sisters and I happily entered our “yam-inals”—fanciful animals—created from oddly shaped sweet potatoes in the “Yambilee” contest. At a festival to our west celebrating all things pork, pretty young women vied to be the Swine Queen, a respectable title, although somewhat unattractive to the ear. At the nearby Cotton Festival’s Tournoi, local men costumed as knights on horseback attempted at galloping speed to lance suspended rings the size of bangle bracelets, broadly labeled as the symbolic enemies of cotton, such as nylon, flood, and the boll weevil. Our Catholic Lenten season began after celebrating Mardi Gras, either with make-believe kings and queens parading in town or the drama of masked paillasses chasing chickens in the country and begging ingredients for a communal gumbo. On Easter Sunday (Pâques), we pocked or knocked decorated Easter eggs to see whose would victoriously remain uncracked. Christmas morning saw dozens of family members—from my great-uncles and aunts to more distant cousins—coalesce into a band of roving revelers toasting the day with a drink at each other’s homes. A great many of these traditions are ongoing. This was the field where the small seeds of my life were planted and nourished in a mix of French and English soil.

Folklorists, linguists, and historians continue to research and document this seedbed. But more personally, the language patterns and traditions passed on to me live in the landscape of my creative writing, mostly in the form of poetry. Grounded in one language or the other, in seasonal or religious traditions, material culture, work, or characters I’ve known, my poems reveal my roots dangling with a little dirt left on. In this journal issue, authors show us how other genres of creative text can sprout from folklore. They share ways to use the folklorist’s tools of close observation, interviewing, and deep listening to trigger connections, to explore, and to craft varied texts. The genres are as diverse as corridos commemorating heroes, outlaws, and notable events in Spanish; memoirs prompted by family or childhood photographs; hair ethnographies in word and picture; family stories rendered as speeches; public and vernacular art and writings that call for social action, visited through collaborative documentation and archiving of material culture; calaveras verses that portray the living as dead; riddles to ponder and decipher; myths told in beadwork; writings reflecting on border walls—both real and metaphorical; and an occupational tradition found in FisherPoetry. You will also see how a museum presents protest art, interviews, and conversations to capture history happening now; how exploration of memorials in the writing process decolonizes a classroom; how a classroom artist’s residency delves into social emotional learning and finding identity through writing Yo vengo de/I am from… poems; how learning about culturally rooted poems can transform children’s understanding of home; and how writing poetry using folklore’s values of context, candor, use, imagination, and love helps students to craft text with authentic purpose and consequences. The strategies offer readers opportunities to consider how the merely personal can contain the universal, how to make genuine connections, how to work toward equity, or how to strengthen social bonds. Additionally, there are classroom connections for several articles. I hope that you enjoy reading this issue and engaging yourself and others in some of the strategies for generating creative text from the seeds of folklore. I think you will be very satisfied if you do!

Sandy Hébert LaBry is a veteran educator from Lafayette, Louisiana, who has taught and administered educational programs in English, French and pedagogy at multiple levels in the K-16 continuum. She has facilitated writing workshops and, as a school district administrator, employed the National Writing Project’s teachers-teaching-teachers model system-wide. She has worked with Local Learning projects in regional schools to integrate folk artists and teaching artists in instruction. Her creative compositions document and transform her own lived traditions, objects of material culture, and interviews with cultural stewards into creative texts exploring such themes as identity, community, relationships, and change.

La grégue de ma grand-mère

reste toujours sur mon fourneau

un don de ma mère sans recette

mais avec une connaissance des rites

de faire le café

dans une manière patiente

lentement

trois cuillères de l’eau bouillante à la fois

et puis trois cuillères de plus

jusqu’à ce que la grégue soit remplie

juste comme nous avons vécu nos vies

nous

ma grand-mère

ma mère

et moi

au fur

et à mesure

comme faire le café dans

la grégue

My grandmother’s drip-coffee pot

still sits on my stove

a gift from my mother without a recipe

but with an understanding of the rituals

of making coffee

in a patient way

slowly

three teaspoons of boiling water at a time

and then three teaspoons more

until the pot is full

just as we have lived our lives

we

my grandmother,

my mother

and me

little

by

little

like making coffee in the

drip pot

–Sandy Hébert LaBry