About the Photos: Designer Jeremy Purser’s fieldwork photography-inspired postcards advertised Growing Right’s Summer 2017 farmers’ market pop-up tour and multimedia website.

In Spring 2015, part way through my first year of public folklore graduate study at Western Kentucky University, I approached Ohio Ecological Food and Farm Association (OEFFA) Education Program Director Renee Hunt fresh on the heels of attending my first OEFFA conference in Granville, Ohio. Breathlessly, I asked whether OEFFA had ever thought about doing an oral history project. I had been documenting sustainable agricultures in Western and South Central Kentucky for the past five months as part of my graduate study, but I was yearning to trace this history as it played out in my own Ohio, where the burgeoning organic farming movement deeply shaped my childhood sense of the interconnections between food, environment, and health. Indeed, Renee replied, OEFFA had dreamed of gathering their history, and for quite some time. From that conversation, and a whole lot of magic from co-conspirators statewide, our project—Growing Right: Ecological Farming in Ohio, 1970s–Now—was born.

With funding from Ohio Humanities, the Greater Columbus Arts Council, and the Puffin West Foundation, Growing Right has conducted 50-plus interviews with farmers, growers, and activists across the state. Moreover, in Summer 2017, the project launched 16 pop-up exhibits at farmers’ markets, grocery stores, and health-conscious food venues across Central Ohio. In September 2017, as an unexpected wrap-up to our tour series, we were accepted to exhibit at Farm Aid, held that year in Burgettsville, Pennsylvania.

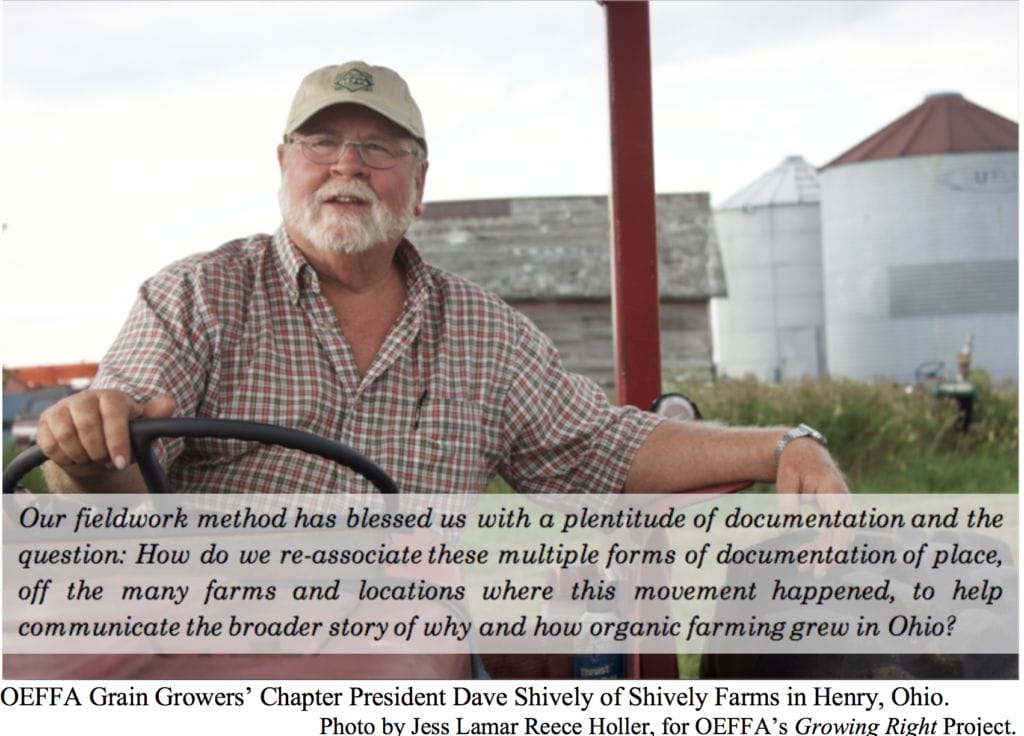

Our project’s documentation methods strove toward an ecological method for public environmental folklife work. We followed in the spirit of folklorists attuned to material culture and vernacular architecture, such as Michael Ann Williams,1 John Dorst, John Vlach, and others, as well as pioneering environmental folklife study projects like Mary Hufford’s Pinelands Folklife Project and the Coal River and New River Gorge projects.2 Growing Right has spent two summers visiting the farms, groceries, and places of Ohio’s organic movement. We documented oral histories and verbal memories of practitioners’ lives in the movement and their synchronicity with their places and ecologies. Thus, we produced a much broader, multimedia fieldwork kit than is standard in oral history practice: hours-long oral history recordings, yes, but also thousands of fieldwork and object photographs, walking interviews, and media-rich farm tours. In our second fieldwork summer, we added acoustic ecology ambient environmental sound recordings, video shorts, and experimental 16mm film. Our fieldwork method has blessed us with a plentitude of documentation and the question: How do we re-associate these multiple forms of documentation of place, off the many farms and locations where this movement happened, to help communicate the broader story of why and how organic farming grew in Ohio?

Growing Right has provided a unique opportunity to mobilize folklife, oral history, and public history documentation methods and forms of public engagement and presentation to share the story of Ohio organics. It has also offered the rare opportunity to develop a truly public-facing popular pedagogy around materials folklorists usually traffic in: oral history, soundscape recordings, walking and working interviews, film and video, and fieldwork photography. Although the field of public folklore has cultivated public programming for venues as diverse as public libraries, narrative stages, and audio/mobile tours for decades,3 Growing Right’s plan for exhibition and engagement also grew out of pop-up models for interaction popular in the current local food scene (where food trucks, pop-up installations, and kitchen takeovers reign supreme) and ideas about the power of ephemeral and sited engagement from the art-for-social-change and public history worlds. Out of this nexus, we decided to share our work where Ohioans shop and eat. Our project, thus, moves in stride with emerging trends in both emplaced and mobile cultural interpretive work and across public history, arts, and museum worlds, to collaborating with audiences, instead of educating them.4

Sharing authority, or, rather, a shared authority, has been a central concern in public folklore, oral history, and public history practice since Michael Frisch popularized the term (1990). Vernacular culture work and the listening arts take the work a step further; often, we folklorists literally collaborate with and co-curate alongside communities of practice. Examples include the Wisconsin Teachers of Local Culture’s cultural tours, developed collaboratively by folklorists, teachers, and community cultural organizations,5 and the community co-curated documentary exhibitions of the Philadelphia Folklore Project, such as the 2016 Tibetans in Philadelphia exhibit.6 Recent volumes in the wider cultural organizing field, like the Pew Foundation’s Letting Go: Sharing Historical Authority in a User-Generated World (2011), following on the heels of calls like Nina Simon’s The Participatory Museum (2010), have pushed the imprimatur for sharing authority in documentation and also in interpretation of fieldwork and public historical materials a step further: beyond the conventional, assumed spaces of public cultural work practice (libraries, archives, universities, museums) and out into new digital realms and on-the-ground places where communities live and work. Mobile and emplaced methodologies—what one panel at the National Council for Public History’s 2016 meeting in Baltimore7 provocatively called “the new mobile public history”—suggest that perhaps public culture work is most effective when produced by and for home audiences and communities and installed locally. This special affordance for social engagement, in the spirit of trans-local organizing, is also created when such work deliberately takes up wheels and shares out across communities.8 It is here, and with our eyes on emplaced, ambient, and existing potential audiences, that we rooted Growing Right’s public programming.

Grassroots Education: The History of OEFFA

OEFFA was founded in 1979 after a Cincinnati based land conservation organization, Rural Resources, called together activists from the Federation of Ohio River Co-Ops (FORC) and upstart and reformed farmers, grocers, and consumers with a bold charge: Why couldn’t the organic, chemical-free food that the burgeoning co-op movement was demanding be grown in Ohio, instead of shipped from organic farms in California and elsewhere? To do that, someone would have to train and educate farmers and consumers in an era when land-grant institutions like Ohio State University thought organics were bunk (Anderson 1983), and they would also have to build, by hand, a new local foods infrastructure. This was Ohio’s nascent organic movement, before it even recognized itself as such.

The first OEFFA conference in 1979, according to project oral history interviews and print cultural sources, drew at least three disparate crowds: “back-to-the-lander” hippies many people might think of when imagining early organic farmers; “salt of the earth” farmers, many well into middle age, who grew up before the age of chemical agriculture and witnessed firsthand the harmful effects of a first generation of American pesticides on their lands, livestock, and bodies; and a new wave of conscientious consumers connecting environmental and health activism to demands for clean food for themselves and their families.

Like so many young movements for social change, early OEFFA was run out of basements, garages, and living rooms, and was catalyzed by homespun print ephemera that don’t often make it into archives: Xeroxed newsletters, flyers, and bulletins did the work of education and policy advocacy, building a virtual imagined community out of a dispersed network of growers, grocers, activists and consumers but also a real community that did political and social work.9 OEFFA’s annual Good Earth Guide—originally a print edition and now an online directory listing all organic producers and ecologically sympathetic grocers and outlets in Ohio—connected participants across the state, made neighbors aware of each other, and helped draw together the early supply-and-demand networks that helped develop a system of farmers’ markets around the state.

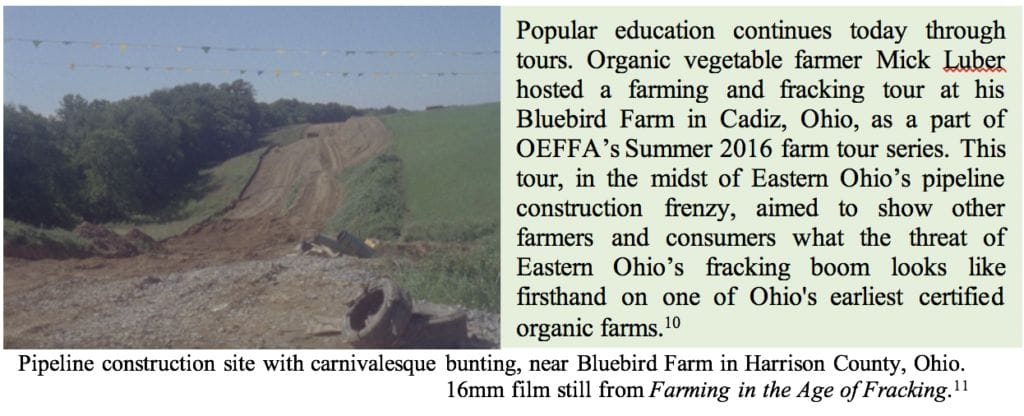

Grassroots and popular education were central to OEFFA from the beginning, too. From that first gathering, what became OEFFA’s celebrated annual statewide conference brought seasoned and new farmers, growers, and consumers together to talk about everything from how to make a profit by growing organic garlic to how to launch direct marketing to the groundwork and policy planning required to establish Ohio’s first set of organic standards. Local chapters took on direct organizing, market cultivation, and policy work from Ashtabula to Athens to the Ohio River. Popular summer farm tours rounded out the program and brought consumers and other farmers directly to successful organic farms to discuss growing methods, animal husbandry, terrain, and environmental challenges and victories. The tours have been a key educational tool. Ohio’s ecological farmers had to band together and teach each other, so place-based and experiential education, in which a farmer invites a crowd to come to her farm and learn how she does it, was the modus operandi for OEFFA and the organic farming movement from its earliest moments.

Grassroots and popular education were central to OEFFA from the beginning, too. From that first gathering, what became OEFFA’s celebrated annual statewide conference brought seasoned and new farmers, growers, and consumers together to talk about everything from how to make a profit by growing organic garlic to how to launch direct marketing to the groundwork and policy planning required to establish Ohio’s first set of organic standards. Local chapters took on direct organizing, market cultivation, and policy work from Ashtabula to Athens to the Ohio River. Popular summer farm tours rounded out the program and brought consumers and other farmers directly to successful organic farms to discuss growing methods, animal husbandry, terrain, and environmental challenges and victories. The tours have been a key educational tool. Ohio’s ecological farmers had to band together and teach each other, so place-based and experiential education, in which a farmer invites a crowd to come to her farm and learn how she does it, was the modus operandi for OEFFA and the organic farming movement from its earliest moments.

Ohio’s organic movement, thus, is a story of polygenesis at its best: a movement formed at the intersection of diverse other social moments, including the women’s movement, spiritual calls to ecological consciousness (Mary Lu Lageman 2017), 1970s anti-strip mining activism in Appalachian Ohio (Rich and Sally Banfield 2016), concern about the toxicity of agricultural chemicals (Ralph Straits 2016), rural-urban food sovereignty programs (Frye 2016), and the farm labor organizing movement in Western Ohio (Shafer 2017)—among others. OEFFA uniquely allowed these various actors to constellate themselves across the state and, through the drafting of state organic standards and rise of OEFFA’s certification program, to build a recognized label for organics to address the growing consumer demand for chemical-free and ecologically produced food.

OEFFA had, of course, grown out of its own storied history, but by 2016 when our project launched, organic foods were more ubiquitous than ever. With so many changes in the players and landscape, OEFFA itself had lost touch with some of the specific history of how this movement came to be. In short, right at a moment when reflection on our movement’s roots to catalyze a stronger future was most critical, our hindsight vision was fuzzy—but our movement history wasn’t yet entirely out of reach.

Together, we saw a window to do radical roots work to bring the stories, activism, and provocation of the early organics movement to the table again for an era of ever-increased climate uncertainty, terrifying new extractive regimes, and continuing corporate and chemical assault on the integrity of our food and water systems. Figuring out how to tell a story about this diverse movement that was already self-aware and rooted in the work of consciousness-raising through place-based participatory instruction and consumer education, however, was a taller order. It turns out the answer was not so much in the how but in the where. A folkloristic perspective and listening-arts based documentary media toolkit, combined with bringing the fruits of our documentation directly to consumers in a farmers’ market setting, helped amplify the sometimes-forgotten stories behind today’s organic movement and directly heighten consumer awareness, and then participation, in the movement through buying organic food.

Thus, (almost) from the get-go, and with some spurs from a visionary state humanities program and a wonderful team of project humanities consultants, we imagined a destiny for Growing Right beyond the archive. Our project amplified the relationship between preservation and access and immediately fueled fieldwork back into the world to foster opportunities, encounters, conversations, and the possibility for social and personal transformation toward a more just world. Thus, popular education was baked into Growing Right’s design before we turned on an audio recorder. Growing Right sought to document a usable past for a grassroots movement before the movement’s founders passed on, yes; but, as critically, we aimed to circulate these stories in the world through a unique pop-up exhibit format, interview indexes created through the Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History’s Oral History Metadata Synchronizer (OHMS) platform,12 and curated multimedia pieces.

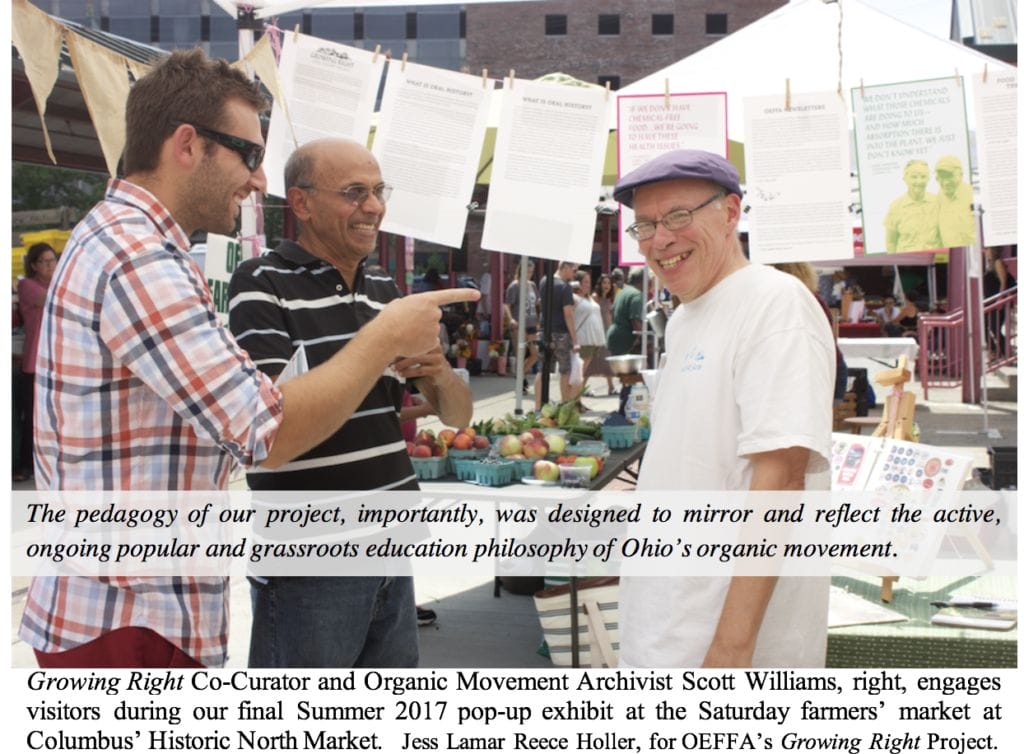

Our vision was to take Growing Right to the streets to bring our project interviews and fieldwork documentation to sites of Central Ohio food shopping encounters to surprise, educate, sometimes delight, and, occasionally, offend. Our pedagogy was designed to mirror and reflect the active, ongoing popular and grassroots education philosophy of Ohio’s organic movement. In this way, Growing Right embodies the spirit of the boots-on-the-ground education work that many of OEFFA’s farmers do at farmers’ markets every week of the growing season, when they share the philosophy, personal beliefs, growing practices, and ecologies of food. We feel good about using this model of education that has worked for 40 years and is emic to the movement, while also extending it to uncovering and commemorating OEFFA’s history and amplifying the stories of the particular people and places who grew today’s movement, whether or not they’re still at market.

Not Just “Expensive Kale”

From the beginning, OEFFA’s consumer education was a sort of counter-education; the ecological farm movement in the late 1970s and early 1980s stood starkly counter to mainstream agricultural education and practice. Growing Right interviews with early organic farmers make clear that the organic movement in Ohio took consumers’ concerns about the impacts of food and agricultural chemicals quite seriously and was deeply influenced by farmers’ negative experiences with chemicals on their own bodies and the ecosystems where they lived and worked.13 The organic movement also dedicated itself to building alternative spaces of access to food grown safely, without toxic chemicals, on farm stands, at farmers’ market, or via a growing network of bold early Ohio natural grocery and cooperative stores. In these spaces people could get organic, Ohio-grown food for themselves and exchange the knowledge that ultimately built our movement.14

Part of our project design endeavored to re-expose the grown-over roots of organic farming as a radical social movement nurtured by consumer advocacy and grassroots environmental activism. Just like the early organic movement exposed the dangers behind chemical pesticides and fertilizers, so too was Growing Right designed to include the labor, voices, perspectives, and concerns of those who had launched the movement but might be occluded from contemporary visibility—especially in the hustle and bustle of a booming local farmers’ market. Thus, in the spirit of the early movement, we pitched our public pop-up exhibits to “all Ohio eaters.” We wanted to reach organic consumers who shopped at farmers’ markets already but might not have thought of the history of organizing that created those markets. We also wanted to reach consumers who might sneer at organic produce, thinking, “It’s just more expensive kale,” and to those for whom food access and affordability is a real issue.

Here, too, a folkloristic perspective proved useful. It was these recalcitrant visitors whom we especially hoped to engage with the stories of the particular people and places that built Ohio’s organics movement. Maybe this engagement wouldn’t or couldn’t change their minds on the kale, but we did hope the history of the movement, shared directly in the voices of its founders, would spark even a quick consideration of why so many Ohio farmers have spent their lives building a healthy, chemical-free foodshed for Ohio and beyond. In the best possible scenarios, we got to talk about what these cautious naysayers felt might make organic food more accessible or possible as a sustainable agriculture for our work.

Early Ohio organic herb farmer Karen Langan, of Mulberry Creek Herb Farms in Erie County, Ohio.

Photo by Jess Lamar Reece Holler, for OEFFA’s Growing Right Project.

Designing Growing Right: The “Where” of the Pedagogy

Growing Right was born as an engaged archival project with plans for a digital exhibit. Working in the vein of many archives and public and local history organizations, we were thrilled to build a critical resource for OEFFA, today’s broader organic movement, and consumers. However, as Stephen High powerfully suggests in his reflection on the inspiring locative, mobile, and otherwise in-situ oral history experiments and public-facing products of Concordia University’s Centre for Oral History and Digital Storytelling, “One wonders, however, if the [I]nternet is the place for deep listening” (2013). After David Merkowitz of Ohio Humanities reviewed an initial draft of our grant proposal for project support, he said something that synced with what High suggests and radically expanded our imagination of places of public encounter: Many a digital public humanities project is born and dies and nobody knows it ever lived at all. What if, he suggested, we got out to do talks or narrative stages about the digital project website as promotion for the project? And what if we did this someplace fitting for the movement, like a farmers’ market? We took David’s idea and ran. We came back with a changed project that mimicked the grassroots popular educational strategies—from farm tours to hands-on workshops—OEFFA has been using to catalyze the ecological food and farm movement in Ohio since the beginning.

History and vernacular culture, it turns out, have much the same problem as an organic farm: They’re often hidden from view. Likewise, not every tomato easily tells her story. Growers at a neighborhood farmers’ market are required to provide a “growing practices” sheet. Growing Right saw that a behind-the-scenes tour or a website is also needed to make visible the arc of the labor and vision behind organic food’s ecologies—ecologies that may be hidden when that tomato shows up, silent, on the table, without the farmer there to narrate. And certainly, the story of the founding generation of Ohio organic growers wasn’t being told at the North Market or Worthington Farmers’ Market on a bustling July day in 2017. To get to that story, you have to squint and imagine back before there were farmers’ markets or even organic labels at all. Visibility is especially an issue for Ohio’s organic grain and dairy farmers, many of whom sell their products on commodity markets and don’t interface and share their stories with customers directly. Growing Right’s public exhibition plan gave us a chance to redirect our sense of our audience from dispersed publics on computers to the incidental audiences at our chosen markets and grocery stores. We could see, talk with, and directly engage with oral histories and fieldwork documentation of Ohio’s original organic farms right as they shopped locally.

Designing for an environmental oral history/folklife pop-up exhibit tour to farmers’ markets and grocery stores also gave us the opportunity to situate our oral histories and transmit sense of place across spaces—sharing the journey organic food takes from farm to market. Thus, our pop-up tour to farmers’ markets and groceries in Central Ohio afforded the chance to cluster the faces, sights, and sounds of a farm in Ashtabula or Clinton County for an audience in greater Columbus. It invited audiences to consider how those local ecologies, the environment to the human labor of building the movement, played into the landscape of Ohio organics. Suzanne Snider of the Oral History Summer School teaches that one of the most powerful effects of oral history recording is to get bodies in a room to experience listening together. These listening parties, as Suzanne calls them, might seem innocuous but are potentially powerful moments of co-witnessing the shared texts of people’s lives. They bring together people who might be changed by an encounter with an oral history recording and do something with that affective experience. Growing Right aimed to do that with our organic movement oral histories and fieldwork photos. Thus, our pop-up’s presence in the ordinary farmers’ market layout—with the pasta vendor or French pastry baker on one side and the family farmstead or pickle lady on the other—could also queer the temporal expectations of the markets and provide a diachronic moment of movement history at the farmers’ market itself. Growing Right sought to create an opening to restore the fuller ecology—cultural and historical—of a market’s organic wares, in the midst of an otherwise unbroken present tense. In an era of “know your farmer, know your food,” the popular education and public folklore work of Growing Right, in celebrating OEFFA’s history and exposing the story of Ohio organics, insists that’s not just an edict that should exist in our neatly bounded contemporary moment.

Farmer Bob Henson, of Henson Family Farm in Clinton County, Ohio, cheers during a viewing of a prototype Growing Right multimedia piece featuring many of his friends and fellow early Ohio organic farmers during Growing Right’s pop-up exhibit at the trade show hall at OEFFA’s 2017 Annual Conference in Dayton.

Photo by Jess Lamar Reece Holler, for OEFFA’s Growing Right Project.

Although our pop-ups were initially designed to advertise our multimedia website and digital public humanities project, they quickly became their own form of public engagement—ephemeral and temporal, sure, but also shot through with the unique pedagogical affordances of the fieldworker and curated clips from fieldwork with Ohio’s founding organic farmers being on site at real Central Ohio farmers’ markets. Embedding our educational work in the farmers’ market space enabled us to engage and document new stories formally, through early experimentation with Michael Frisch’s PixStori app and vox pop field recording and photography of shoppers interacting with our exhibit, and via unrecorded conversations and exchanges with those wandering into the booth. Not unlike the project website, however, the pop-up exhibit tour also performed a telescoping scale of place within the locations and contexts we chose for exhibition. Although we could only set up our tent at one market or grocery at a time, our presence signaled and made explicit the actual multiplicity of places, locations, ecologies, movements, and times that made up the organic movement across its history.

Folklorist Jess Lamar Reece Holler poses with a seedling and a Growing Right pop-up tour rack card at one of the exhibit’s three installations at the Franklin Park Conservatory Farmers’ Market, Columbus.

Photo by Christie Nohle, Franklin Park Conservatory and Botanical Gardens.

Co-Curation All the Way Down: Collaborating Within the Movement

Our exhibit project brought together two strands: our ongoing fieldwork project documenting oral histories and media from farms and other locations across the state and the print cultural history. Our chief collaborator in this latter effort was Scott Williams, an early FORC activist, early OEFFA member, and ecological food and farm movement community archivist. I met Scott in the audience at OEFFA’s 2015 conference, where a narrative stage that became the early inception for this project was being convened by folklorist and rural sociologist Howard Sacks of Kenyon College’s Rural Life Center. From a seat next to mine, Scott regaled me with horror stories of the day when farmer, co-operative activist, and early OEFFA member Mick Luber brought a binder of photos of the movement’s early days to an OEFFA conference in the mid-1980s, to a “recap of the early days” panel. The event was packed, conversation afterward was great, and, in the shuffle, Mick’s binder was lost. With it, decades of pictorial evidence of the movement disappeared. Luckily, despite such mishaps in OEFFA’s memory keeping, the movement has Scott. Trained in archival work and president of the Columbus chapter of the Aldus Society for Rare Books, Scott has spent the past 40-odd years unofficially maintaining an archive of early print ephemera from the ecological food, farm, and co-operative movements in Ohio, including pamphlets, the early run of OEFFA newsletters, marketing brochures, historic editions of OEFFA’s Good Earth Guides … and 30 years’ worth of organic food labels.

Scott’s collection became the basis for the print culture part of our exhibit and helped diversify its voice. We took clear curatorial steps to ensure the public understood the organic movement was built by people, so it was important not to back-impose a monolithic story on that history. As such, Scott decided on several categories of print materials at the hinge of the other movements that birthed it and continued alongside Ohio’s organic food and farm movement—like the Midwest’s historic co-operative movement. Ultimately, our pop-up exhibit showcased a rotating set of “curated” facsimile documents in five broad categories: OEFFA newsletters, brochures, miscellaneous and oversized documents, the history of the co-op movement, and the history of food labels. In keeping with best practices in museum studies and the public humanities,15 Scott and I worked together to co-curate his collection: first, through mini-oral history interviews on the provenance of each items in his collection and then, through many cycles of co-writing. The finished item-level labels are in his voice, with the larger exhibit-level labels featuring two sections—my commentary from the vantage of synthesizing the fieldwork together with these print cultural sources and Scott’s as the collector and curator who has stewarded these materials over the years and directly participated in their making.

Although it admittedly baffled some, the exhibit also worked to foreground the process of its own curation: Scott’s decades of collecting and my fieldwork and documentation process. Rather than mystify the journey from dispersed statewide social movement to nonprofit organization to oral history and folklife exhibition, we decided to show our seams and turn that process inside out. We chose this for fellow methods geeks like ourselves and to demystify the organic movement and portray it as an active grassroots effort that grew with every little contribution and came to influence how Americans could access and demand information about food origins in major ways (like food labels).

Jeremy Purser’s custom-designed oral history posters at Growing Right’s two-week installation at the Keller Market House—a regional foods aggregator housed in a historic grocery store in downtown Lancaster, Ohio. Poster design and idea based on Clara Gamalski’s (free snacks) project, documenting class and food choice preferences in Pittsburgh.

Politics of the Excerpt: Designing for Ambient Attentions

A major challenge and opportunity was how to display long-form oral histories, interviews, and audio farm tours in a pop-up setting, designing not for event-based attention (like a more conventional documentary screening or public folklore narrative stage) but for ambient, wandering, interruptive, and interrupted attentions.16 After discussions with our public humanities consultants, we knew we had about three minutes to hook people on-site. Any further engagement would rely upon interest generated through those three minutes and the snappy design of our project postcards. These linked to our website and each referenced a different Ohio farm, farmer, or grocer featured in our interviews. Modular design thus was critically important. Riffing on the model of the Southern Foodways Alliance modular toolkit, which includes a full-length oral history, representative photography sample, and short slideshow, we created a series of short multimedia slideshows to accompany our long-form interviews. Some focused on particular farmers and others, like our chemicals and health piece, offered similar and contrasting experiences across multiple farms, locations, and generations to give a diverse perspective on how a particular issue or concern manifested in Ohio’s ecological food and farm movement.

Excerpting a full-length history to a digestible multimedia short, of course, is a political act. Who gets to say what part of someone’s life story, labor history, and movement involvement makes the cut? Moreover, narrative moments that “pop” for a visitor to catch a narrative of someone’s life may not be the ineffable moments and attitudes that define a person’s sense of ecological attachment and entanglement—the primary thing we sought to communicate. Thus, much of the time (and in presentations we’ve shared on the project) we went for conversion stories, which cropped up across many interviews in which farmers define a particular moment or event that brought them to organic farming work. Other pieces simply introduced the farmer and tried to go “beyond the human,” following recent attentions to multi-species ecological method,17 to give a sense of a life in organic work. Our pop-up eventually adopted a multimodal strategy: We presented formats and listening/viewing opportunities ranging from full-length oral histories (over headphones or speaker), short multimedia pieces, and donated iPods fitted with ambient/ environmental soundwalks from farms across Ohio.

Pop-up visitors watch and listen to a multi-media short piece during Growing Right’s most-visited pop-up installation, outside of Westerville’s Raisin Rack Natural Foods Market.

Photo by Jess Lamar Reece Holler, for OEFFA’s Growing Right Project.

Although it made for less strongly curated visitor experiences and opened the floodgates for multiple interpretations, we found that there was something more honest in displaying our full-length oral histories and offering the chance to drop the cursor wherever they wanted. They could understand they were hearing part of a longer, more contextualized encounter rather than a cleaned-up, didactic excerpt with one pinned-down intervention. Critically, however, the short pieces allowed us to show sense of place and give visitors a rich sensory encounter with a mediated framing of the farmer’s places and ecologies, vistas that unintentionally might get occluded at the farmers’ market and grocery store. These images, rotating at four-seconds-per-image speed baked into the iMovie software, allowed a different scope and scale to our short pieces that perhaps countervailed the tidy, necessarily incomplete audio excerpt.

Importantly, we presented multimedia experiences on an iPad atop vintage orchard crates juxtaposed with a set of static, pop-art designed oral history posters, envisioned by our graphic designer on the model of food studies scholar and activist Clara Gamalski’s (free snacks) installation in Pittsburgh. Each poster presents one narrator with a quote from the interview. Designed in an arresting pop-art style in bright neons, the posters formed a backdrop “quilt” to the exhibit and allowed an ordinarily time-based narrative medium (oral history), as well as the wide scope and range of the project’s narrator pool, to connect visually all at once. We weren’t, of course, off the hook with the politics of the excerpt. We tried to select a variety of quotes on different topics—the toxic smell of pesticides that drove one young grain farmer to convince his father and brother to farm organically, the importance of risk for entrepreneurship, the small miracles and big politics of ecological stewardship—so we weren’t just using our narrators to spew some central vision of organics. Ultimately, the short quotes we chose and the posters went up on a particular day, influencing the message of the overall booth.

The project benefited enormously from our partnership with Jeremy Purser of Slow Poach Design—a farm and kitchen worker, and an experimental sound artist who happened to be a former junior designer at Modern Farmer magazine. In our graphic design collaboration, we tried to design for the same ecological consciousness we wanted to inspire or invite in our potential audiences. Our design approach, from the main font to posters, postcards, and rack cards evoked bright 1980s themes and reflected the visual culture of the era of the rise of OEFFA, organic farming certification standards, and solidification of the movement in Ohio.

Importantly, our bold 1980s-meets-ethnography look wasn’t what people expected when they thought of organic farming. Inundated with images of carrots, baskets, straw hats, and roosters, we wanted to push the dominant (and maybe stale) farmers’ market/organic farming visual culture to show the wider labor and ecologies behind popular organic farming narratives. Thus, our postcards pushed the chickens to the side of the frame and foregrounded the free-range lawn the chickens were pastured on, for example. Some popular images from the series of 12 postcards didn’t show people or food at all. Instead, they showcased the places, processes, and material culture of the behind-the-scenes lives that made this movement possible: stacked pastel-sea-foam cordwood with a pale pink border or a deep-blue-and-powder-pink rendition of grain farmer David Bell’s basketball hoop inside his soaring barn. We tried to embody environmental humanities methods in our rack card design, as well, with a checkerboard pattern drawing together dozens of fieldwork images of plants, hands, barn cats, pups, goats, chickens, and grains from across the state in a broad movement ecology. The rack card, which explicitly advertised our summer 2017 pop-up tour dates and locations, also served as a “grand scale” statement of our project’s reach and interacted nicely with the postcards, each featuring a specific farm and place documented in the project.

We released our project postcards in seasonal batches to reflect the tides of Central Ohio farmers’ markets. The first set launched in February in time for the annual OEFFA conference, an early May set marked the onset of spring produce, and a high-summer set launched as tomatoes hit the markets, and we hoped the limited-edition, designer-made sets would draw people back across the season, or lure them to follow our tour across multiple markets. We’re not totally sure if it worked—or if anyone explicitly came back to visit our exhibit at different farmers’ markets over the course of the summer just so that they could gather up a complete set of project postcards—but we’d like to think we helped inspire some seasonality in our pop-up exhibits, to match the spirit of the farmers’ markets.

Ecological Method: Toward a Public Environmental Humanities?

All told, Growing Right’s pop-up exhibits have been about a simple question: What happens when we surface, show up, and interpret out (and out loud, on-site) the sometimes-lost, sometimes-forgotten, and sometimes-deliberately-obscured histories of the people, places, and labor behind our food, and the environmental impacts of how that food is grown…in the middle of a bustling market or grocery store? Ultimately, through our site-based exhibition practice, we’ve hoped to inspire changes of heart—sudden, surprising, and newfound attention to the larger economic, environmental, labor, and organizing ecologies that have made our now-robust and still-growing organic food and farm system possible. At the end of the day, of course, it’s difficult to measure impact. Was Growing Right successful? We can’t measure the pop-up tour’s influence on increased purchases of organic food or epiphanies. We’ve counted the modest boost in traffic to our website and YouTube oral histories after pop-up events, but in an era of standardized results our experiment has also been about a radical hope in an unfolding audience encounter, which may bloom then and there in the moment or spring up years down the line. These are the sorts of attention—a gradual orientation toward a whole way of seeing, a gradual inability to cordon off the risks and harms of agricultural chemicals to the people and communities most in danger of exposure and accumulation—that birthed Ohio’s organic movement. Following Martha Norkunas, we hope we’ve provided the space for encounter with the kind of deep “listening across differences” (2009) that might slowly suggest, on the strength of OEFFA’s founding farmers’ narratives and places, the planetary urgency of another way of connecting.

Looking ahead toward another Farm Bill, ongoing public debates about the toxicity of Monsanto’s RoundUp/glyphosate (Gillam 2017), increasing explosions and uncertainty for fracked communities in Southern and Eastern Ohio,19 and legality of repurposing and storage of toxic frack waste across the rest of the state, Growing Right hopes to take another leap with these local stories of movement-building, organizing, and resistance. In 2018–2019, we plan to launch a pilot podcast series; adapt our long-form oral histories, soundscape recordings, and walking and process interviews for a series of short documentary pieces for broadcast radio; edit a short experimental film on the impacts of nonconventional hydraulic fracturing and injection wells on Ohio organic farms; and publish our full series of OHMS-indexed interviews with curated fieldwork photography for OEFFA’s 40th anniversary in February 2019. While our pop-up tour may have been a temporary experiment, our work mirrors the everyday advocacy and education our farmers do every season, whether from the farmers’ market tent, the tractor, or lobbying in Washington, DC. We hope Growing Right provides a provocative example for how nonprofit agricultural, environmental, and citizen science organizations can collaborate with and through the public environmental humanities and long-established vernacular listening arts to encourage the divestments from toxic heritages and investments in regenerative practices necessary to combat a damaged food system in an era of ever-more urgent environmental crisis. Let’s usher in a new area of public environmental folklife devoted not just to telling the stories, but also staging encounters that just might finally be adequate to our (chemically-burdened), ecologically imperiled world.20

Acknowledgements OEFFA Staff: Renee Hunt, Milo Petruziello, Lauren Ketcham, Eric Pawlowski, Amelie Lipstreu, Julie Sharp, Carol Cameron; and Executive Director Carol Goland; and more; the Growing Right Project Team (Carol Goland, Brooke Bryan, Howard Sacks, Danille Christensen, Sara Wood, Scott Williams, and Jeremy Purser); Suzanne Snider; Cristina Kim and the Berkeley Oral History Program; Mary Hufford and Jeff Todd Titon (for the inspiration and faith); The American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress (special thanks to Todd Harvey, Judith Gray, Michelle Stefano, and Nancy Groce, and to the support of a 2016 Parsons Award); Doug Boyd at University of Kentucky Libraries’ Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History; the Oral History Association and Oral History in the Mid-Atlantic Region; the good humans of the Oral History Undercommons; WKU Folk Studies; Erin Bernard and the Philly History Truck; Clara Gamalski; Cory Fischer-Hoffman (and classmates Lauren Kelly, Amanda Ruffner, and Megan Pellegrino-Zubricky); The Penn Museum; David Merkowitz and Ohio Humanities; Allison Barret and the Greater Columbus Arts Council; Java Kitrick and Puffin West Foundation; OEFFA’s Board and Board President/urban farmer Rachel Tayse; the incredible network of 50-plus farmers who allowed temporary invasion of their homes for project fieldwork and shared incredible stories with the project and grew this movement; half a dozen farmers’ markets and grocery stores in Central Ohio and their intrepid managers and volunteers; Della, Enrique, and the entire staff at FedEx Easton printing center; Jeff and Isaly Caledonia for the fieldwork companionship, co-piloting, and occasional barking; and everyone else who helped and came out to listen.

Jess Lamar Reece Holler is a community-based folklorist, public historian, cultural worker, and documentarian in the emergent interdisciplinary field of public environmental humanities. Her work focuses on vernacular experiences, mediations, and organizing around health, labor, everyday toxicity, and attachments to place. She runs Caledonia Northern Folk Studios, a multimodal documentary arts, folklife, public history, and oral history consultancy in Columbus and Caledonia, Ohio. Reach her at oldelectricity@gmail.com and via caledonianorthern.org.

Carol Goland (Project Humanities Consultant/Executive Director OEFFA) holds a PhD in Anthropology from the University of Michigan and is Executive Director of the Ohio Ecological Food and Farm Association. She is an ecological anthropologist who previously taught Environmental Studies at Denison University. Reach her at cgoland@oeffa.org.

Jeremy Purser (Project Designer) is a graphic designer, kitchen worker, farm laborer, and experimental musician based in Durham, North Carolina. He runs Slow Poach Design, see slowpoach.com (sounds) and jeremypurser.com (design). Reach him at jeremypurser@gmail.com.

Scott Williams (Project Co-Curator) is a grant writer, community archivist, rare books collector, lifelong activist with Ohio’s co-operatives movement, and early OEFFA member. He lives in Columbus, Ohio. Reach him at scott.williams99@att.net.

For correspondence about the project, reach out to growingrightproject@gmail.com.

URLs

Philadelphia Public History Truck: https://phillyhistorytruck.wordpress.com

Manitoba Food History Project: https://www.manitobafoodhistory.ca

A People’s Archive of Police Violence in Cleveland: http://www.archivingpoliceviolence.org/purpose

Anti-Eviction Mapping Project: https://www.antievictionmap.com

FracTracker Alliance: https://www.fractracker.org

Basilica Hudson (Automotive Archive, A Roving Memorial): http://basilicahudson.org/tag/suzanne-snider

The Laundromat Project: http://laundromatproject.org

Wage/Working: http://wageworking.org

Smithsonian.com: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/phone-booths-are-back-times-squareand-time-theyre-telling-immigrant-stories-180963879

Concordia University (Centre for Oral History and Digital Storytelling): http://storytelling.concordia.ca

Concordia University (A Flower in the River): http://storytelling.concordia.ca/projects/flower-river

Oral History Summer School: http://www.oralhistorysummerschool.com

The Rural Life Center: http://www.rurallifeatkenyon.com

Southern Foodways Alliance: https://www.southernfoodways.org/oral-history/

Endnotes

- For a concise history of tensions between folklore studies and material cultural, environmental, and vernacular architectural attentions, see Michael Ann Williams’ 2015 American Folklore Society Presidential Address, in print as: Williams, Michael Ann. 2017. After the Revolution: Folklore, History, and the Future of Our Discipline. Journal of American Folklore. 130.516: 129-41. Video recording available via the American Folklore Society here: https://youtu.be/6nu3krNSeDY.

- This research, ongoing, was first generously sponsored through a 2016 Parsons Fellowship at the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, in collaboration with Jeffrey P. Nagle, environmental, labor, and technology historian. For more on these important early cultural conservation and environmental folklife collections, many spearheaded by folklorist and cultural organizer Mary Hufford, visit the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, or see the Tending the Commons: Folklife and Landscape in Southern West Virginia digital exhibit at https://www.loc.gov/collections/folklife-and-landscape-in-southern-west-virginia/about-this-collection.

- See Jens Lunds’ and Jill Linzee’s work in Washington State with the Northwest Heritage Resources’ Audio Tour Guides, AKA the Heritage Audio Tour Guides. For more information or to order, see Washington Folk Arts // Northwest Heritage Resources http://www.washingtonfolkarts.com.

- Nina Simon. 2010. The Participatory Museum. Santa Cruz: Museum 2.0; Seriff, Suzy. 2016. Like a Jazz Song: Designing for Community Engagement in Museums. Journal of Folklore and Education, 3: 3-7. See also http://www.locallearningnetwork.org/journal-of-folklore-and-education/current-and-past-issues/journal-of-folklore-and-education-volume-3-2016/like-a-jazz-song-designing-for-community-engagement-in-museums for other writing on participatory museum culture.

- See the Wisconsin Teachers of Local Culture webpage and professional development resources at https://wtlc.csumc.wisc.edu and teacher-led cultural tours at https://wtlc.csumc.wisc.edu/teaching/teacher-led-cultural-tours.

- See project page at the Philadelphia Folklore Project website http://www.folkloreproject.org/gallery/tibetans-philadelphia.

- See National Council for Public History 2016 Program Guide for Challenging the Exclusive Past, Alternative Modes of Engagement: Social Curation and the New Mobile History, featuring Michael Van Wagenen, Bill Adair, Erin Bernard, and Michael Frisch, http://ncph.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/2016-Annual-Meeting-Program-Final-Web.pdf. See also Erin Bernard, The Philly History Truck https://phillyhistorytruck.wordpress.com and “A Shared Mobility: Community Curatorial Process and the Philadelphia Public History Truck,” in Exhibitionist https://static1.squarespace.com/static/58fa260a725e25c4f30020f3/t/594c479fe6f2e13236a10209/1498171332219/15+EXH+Studies+Bernard+EXH+Spring+2015-15.pdf.

- Fischer-Hoffman, Cory with Amanda Ruffner, Lauren Kelly, Megan Pellegrino, and Jess Lamar Reece Holler. 2016. Online and Off-Line Memory-Keeping: New Technologies for Community-Based and Non-Traditional Archives, co-organized/presented at the Oral History in the Mid-Atlantic Region (OHMAR) 2016 Annual Conference. Hagley Museum. Wilmington, Delaware. April 14-16.

- See“Harv Roehling, Locust Run Farm — Oxford, Ohio [FULL-LENGTH], https://youtu.be/zWbWsTypUvQ. Multimedia piece produced from oral history interview, conducted by Jess Lamar Reece Holler for Growing Right. May 31, 2016. Oxford, Ohio. Also see Locust Run Farm, OEFFA’s Good Earth Guide. http://www.oeffa.org/userprofile.php?geg=207.

- See Take a Farm Stand Tour, in OEFFA’s 2016 Ohio Sustainable Food and Farm Tour Series, via https://lucas.osu.edu/sites/lucas/files/imce/LocalFood/OSU%202016%20Farm%20Tours.pdf, pp. 7; and Mick Luber’s Bluebird Farm, via OEFFA’s Good Earth Guide http://www.oeffa.org/userprofile.php?geg=1385.

- Growing Right’s experimental film on the impacts of fracking and extraction on organic farms in Eastern Ohio. Film produced through a Program Support grant to OEFFA, from the Greater Columbus Arts Council (GCAC).

- For more on OHMS and its rise out of the landscape of digital access demands for oral history archives and repositories, see Boyd, Douglas A. 2014. ‘I Just Want to Click on It To Listen’: Oral History Archives, Orality, and Usability. In Oral History and Digital Humanities: Voice Access and Engagement, eds. Douglas Boyd and Mary Larson. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. To index your oral history or folklife collection via OHMS, see the Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History’s excellent website: Oral History Metadata Synchronizer: Enhance Access for Free. The Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History at the University of Kentucky Libraries, http://www.oralhistoryonline.org. Excellent resources on oral history indexing aimed at students and educators in liberal arts contexts (but useful for community scholars and others) are also available via the Great Lakes Liberal Arts Consortium’s Oral History in the Liberal Arts (OHLA) initiative portal at http://ohla.info. Folklorists and cultural workers will also appreciate OHLA collective member and Oberlin College professor Ian MacMillen’s thoughtful project blog post, Between Oral History and Ethnography, http://ohla.info/between-oral-history-and-ethnography.

- See multiple project interviews, most available at Growing Right Project’s homepage growingrightproject.com. Especially relevant here are interviews with Mick Luber, Bluebird Farm, Daryl, Diane and Denis Moyer of Moyer Brothers Farm, David Bell of Paul Bell & Sons Farm, and the Greggs of Gregg Farms.

- For project interviews focused on the early history of natural foods markets, grocery stores, and co-operatives, see interviews with Sally and Jon Weaver-Summer, Margaret Nabors, Ed Perkins, Mick Luber, Scott Williams.

- See for example Murawski, Mike. Object Stories: Rejecting the Single Story in Museums in Art Museum Teaching, https://artmuseumteaching.com/2012/12/26/object-stories-rejecting-the-single-story-in-museums; the Portland Art Museum’s Object Stories https://portlandartmuseum.org/objectstories; and any work of the Philadelphia Folklore Project www.folkloreproject.org.

- These reflections have been shaped by conversations with Shilarna Stokes as well as with project humanities consultants Howard Sacks, Brooke Bryan, Danille Christensen, and Sara Wood and Carol Goland, Scott Williams, and Jeremy Purser.

- For more on multispecies ethnographic method in fieldwork, see Tsing, Anna. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press; and Kohn, Eduardo. 2013. Thinking Like a Forest: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- An inspiration for a product that creatively uses these media materials is Charlie Hardy and Alessandro Portelli’s pioneering early experimental oral history audio essay, I Can Almost See the Lights of Home. For more visit the digital project in The Journal for Multimedia History, Vol. 2, https://www.albany.edu/jmmh/vol2no1/lights.html. For Charlie Hardy’s reflections on the making of the project, see Hardy, Charles III. 2014. Adventures in Sound: Oral History, the Digital Revolution, and the Making of ‘I Can Almost See the Lights of Home’: A Field Trip to Harlan County, Kentucky. In Oral History and Digital Humanities: Voice Access and Engagement, eds. Douglas Boyd and Mary Larson. New York: Palgrave MacMillian.

- See “Fracking and Farmland: Stories From the Field,” via OEFFA’s Farm Policy Matters for more information at http://policy.oeffa.org/frackingfarmland.

- This concept of “staging the encounters that just might finally be adequate to our (chemically-burdened), ecologically imperiled world” should be credited to Mary Hufford, email messages to author, January-March 2016. See also Hufford, Mary. Working in the Cracks: Public Space, Ecological Crisis, and the Folklorist. Journal of Folklore Research. 36.2/3: 157-67.

Works Cited

About the Laundromat Project. 2014. The Laundromat Project. Accessed June 8, 2016, http://laundromatproject.org/who-we-are/about.

Anderson, Benedict. 1983. Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism. London and New York: Verso.

Bernard, Erin. The Philly History Truck. Accessed April 10, 2018, https://phillyhistorytruck.wordpress.com.

Blakemore, Erin. 2017. Phone Booths are Back in Times Square—and This Time, They’re Telling Immigrant Stores. Smithsonian Magazine, June 30. Accessed April 10, 2018, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/phone-booths-are-back-times-squareand-time-theyre-telling-immigrant-stories-180963879.

Drake, Jarrett, et al. 2015. A People’s Archive of Police Violence in Cleveland. Accessed April 10, 2018, http://www.archivingpoliceviolence.org/purpose.

Frisch, Michael. 1990. A Shared Authority: Essays on the Craft and Meaning of Oral and Public History. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Frye, Charlie. Oral History Interview, conducted by Jess Lamar Reece Holler for Growing Right. June 21, 2016. Sullivan, Ohio. Unpublished.

Gillam, Carey. 2017. Whitewash: The Story of a Weed Killer, Cancer, and the Corruption of a Science. Washington, DC: Island Press.

High, Steven. 2013. Embodied Ways of Listening: Oral History, Genocide, and the Audio Tour. Anthropologica. 55.1: 76.

Holler, Jess Lamar Reece. 2017. Noisy Recordings: or, Oral History and Its Ecologies. [Workshop] Oral History in the Mid-Atlantic Region Annual Conference.

—. 2011. Oral History in the City. Columbia University // Union Theological Seminary. Pew Foundation’s Letting Go: Sharing Historical Authority in a User-Generated World.

Mary Lu Lageman—Grailville Community [Clermont County] via Growing Right on YouTube https://youtu.be/8KL3vCZTxjc Multimedia piece produced from oral history interview, conducted by Jess Lamar Reece Holler for Growing Right. June 1, 2017. Loveland, Ohio.

Norkunas, Martha. 2009. Listening Across Differences. Smithsonian Education, September 25. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AKbTMta6Ku8.

Pezzulo, Phaedra. 2007. Toxic Tourism: Rhetorics of Pollution, Travel, and Environmental Justice. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Projects. FracTracker Alliance. Accessed May 15, 2018, https://www.fractracker.org/projects

Ralph Straits—Straits Brothers Farm [Holmes Co.] via Growing Right on YouTube https://youtu.be/Aydq_HEE6xI Multimedia piece produced from oral historyiInterview, conducted by Jess Lamar Reece Holler for Growing Right. July 29, 2016. Killbuck, Ohio.

Rich and Sally Banfield — Mt. Perry, Ohio [FULL-LENGTH] via Growing Right on YouTube https://youtu.be/9ruKJovDhzg Multimedia piece produced from oral history interview, conducted by Jess Lamar Reece Holler for Growing Right. June 12, 2016. Mt. Perry, Ohio.

Simon, Nina. 2010. The Participatory Museum. Museum 2.0.

Shafer, John. Oral History Interview, conducted by Jess Lamar Reece Holler for Growing Right. June 3, 2017. Ada, Ohio. Unpublished.

Snider, Suzanne. Automotive Archive: A Roving Memorial. Basilica Hudson. Accessed April 10, 2018, http://basilicahudson.org/tag/suzanne-snider.

Titon, Jeff Todd. 2016. Environmental Humanities, Music, and Sustainability. Sustainable Music, October 31. Accessed April 10, 2018, https://sustainablemusic.blogspot.com/2016/10/environmental-humanities-music-and.html.

—. 2017. Ecojustice and Folklife (Yoder Lecture), from the 2017 Annual Meeting of the American Folklore Society (Minneapolis, Minnesota), Accessed April 20, 2018 at https://youtu.be/tIpSR0XvdDg.

Thiessen, Janet. 2018. Food (History) Truck. Manitoba Food History Project @ The University of Winnipeg, February 1. Accessed June 6, 2018, https://www.manitobafoodhistory.ca.

Visualizing Bay Area Displacement and Resistance. The Anti-Eviction Mapping Project. Accessed April 10, 2018, https://www.antievictionmap.com.

Watson, Tennessee and Lauren Hadden. Events & Exhibitions. Wage/Working Project. Accessed June 8, 2018, http://wageworking.org/new-events.