We are a group of youth in Pittsburgh who want to show the world that despite being displaced and sometimes forgotten, we have not forgotten who we are and what we have to offer the world. Our story is one of survival and of hope. We may be the Children of Shangri-Lost, but we have found ourselves in our new homes around the world.

We are a group of youth in Pittsburgh who want to show the world that despite being displaced and sometimes forgotten, we have not forgotten who we are and what we have to offer the world. Our story is one of survival and of hope. We may be the Children of Shangri-Lost, but we have found ourselves in our new homes around the world.

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, is home to approximately 5,000 Bhutanese refugees who are building a thriving community of newcomers. In our “City of Bridges,” young Bhutanese have purposefully created a website and a community organization, which the welcome above proudly introduces, that have great potential to introduce different communities and cultural traditions. The website is only the most visible face of a much larger set of cultural endeavors. Young adults in Pittsburgh’s Bhutanese immigrant community share their dynamic, evolving folklife through Children of Shangri-Lost (COSL), a nonprofit organization. Together, COSL members curate an impressive set of social media projects and promote public forums that celebrate their traditional forms of cultural expression. They reach out to their new neighbors and proactively approach writing new narratives of where they have come from and who they are becoming. These resources can provide educators a dynamic model of ways that others can appreciate and incorporate lessons from their difficult journey toward full participation in the United States.

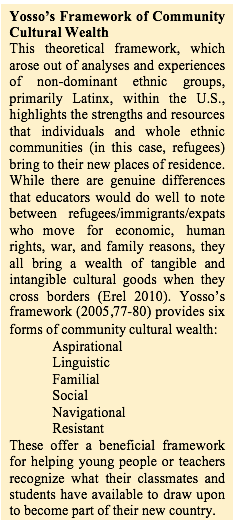

These new immigrants’ strategic, savvy use of new media forms as explicit means of outreach and renewal offers a welcome contrast to increasing public discourses of hate, exclusion, entitlement, and “parasitic” immigrants. It directly counters a deficit discourse about diasporic communities. Instead, they spotlight the shared human saga of their displacement, the folk practices they are actively maintaining, and their aspirations for greater belonging within their host society. By highlighting varied forms of folklife and ways of knowing, for example, dance, poetry, video montages, and blogs, COSL posters’ words and actions demonstrate the community cultural wealth (Yosso 2005) their community possesses and contributes to their new home. Further, by providing thoughtfully curated first-person accounts and promoting events open to their larger neighborhoods, COSL models how newcomer communities can dynamically share their folklife traditions as the foundation for constructing bridging social capital (Putnam 2000).

Young adults’ poignant struggles to create a transcultural identity provide a rich, ever-growing witness for educators who wish to incorporate first-person accounts of resilience and intercultural dialogue into their teaching. That COSL is largely a youth initiative makes it all the more appealing to other teens and young adults whose natural curiosity about identity and belonging is piqued at this time of their lives. We believe that COSL’s core activities are therefore particularly important expressions of folklife that can contribute richly to educational endeavors far beyond the borders of the city they now call home.

In this article, we first contextualize the folk group’s worldwide saga of repeated cycles of displacement and integration. We then introduce COSL as a grassroots folklife organization significantly contributing to this community’s well-being in their newest hometown, Pittsburgh. Next, we consider the importance of shifting populist discourses of deficit to acknowledgments of community cultural wealth and of shifting from norms of segregation and stereotyping to creating effective events that bridge social groups. In each, we offer examples, taken from the recent COSL repertoire, of resources of particular interest to folklife-inspired educators, along with open-ended considerations about their practical use as part of a larger project of social justice.

The Lhotsampas of Bhutan Become a Diasporic Community

COSL’s very name is a call to the mythical as well as the human rights elements of a displacement and resettlement saga. For generations, Bhutan’s beautiful, mountainous kingdom counted among its many ethnic populations a Nepalese-speaking Hindu population known as Lhotsampas, or “People of the South.” This group emigrated from Nepal to Bhutan to farmland in the south of the country. While they considered and still consider themselves Bhutanese, most maintained their Hindu religion and traditions, including their Nepalese language and customary dress, a key marker of their folk group. Bhutan’s Nationality Law, passed in 1958, formally granted them full citizenship (Cultural Orientation Resource Center 2007; Hutt 2003; Rizal 2004).

Three decades later, Bhutan’s government, observing intra-national conflicts in neighboring countries, was concerned by the growth of the Lhotsampa population and feared that the country would lose its national and religious (Buddhist) identity (Hutt 2003). Thus began Bhutanization, aimed at “unifying” the national culture. Policies included imposing the language, dress, and Buddhist religion of the majority Druk culture. Protests, largely organized by another group of young adults (university students), were met with Bhutanese military force, who accused Lhotsampas of being illegal immigrants and then confiscated their land in addition to arresting and torturing protestors. In the early to mid-1990s, tens of thousands were forced to flee to refugee camps in neighboring Nepal (Cultural Orientation Resource Center 2007; Rizal 2004; Zeppa 1999). There they were to stay for up to two decades, with approximately 10,000 displaced Bhutanese still in limbo today (Preiss 2016).

In 2003, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) announced it would seek resettlement rather than repatriation for these refugees. In 2006, the U.S. announced a program to take up to 60,000 (Cultural Orientation Resource Center 2007). As of March 2016, approximately 85,000 Bhutanese refugees have resettled in the U.S. (“Bhutanese Refugees Find Home in America” 2016). Of those, nearly 10,000 have resettled in Pennsylvania. (This number does not account for secondary migration to Pennsylvania by refugees who were resettled in other states and then decided to relocate).

The outcome of this wide dispersal is that Bhutanese stories of displacement and resettlement thus resonate with other diasporic communities’ sagas of their ongoing struggle for human rights, sovereignty, and transcultural identity. Thus, COSL’s choice of Internet-based social media tools is both apt and effective. COSL’s logo thoughtfully integrates their past and current storylines, and could serve as a catalyst for an introductory lesson merging historical and visual literacy. It depicts a core folklore element, their origin story of coming to a new homeland, and its centrality in shaping their current discourse of resilience and new beginnings. The logo shows a family, intact and holding hands, walking upright into an unknown future. The fading color of their path symbolizes traversing a dangerous liminal state as they leave their family homes, stripped of their national identity. The sun behind them sets over their homeland. But they move forward, and COSL tells the world of their past and present, as well as their hopes and plans for the future.

The outcome of this wide dispersal is that Bhutanese stories of displacement and resettlement thus resonate with other diasporic communities’ sagas of their ongoing struggle for human rights, sovereignty, and transcultural identity. Thus, COSL’s choice of Internet-based social media tools is both apt and effective. COSL’s logo thoughtfully integrates their past and current storylines, and could serve as a catalyst for an introductory lesson merging historical and visual literacy. It depicts a core folklore element, their origin story of coming to a new homeland, and its centrality in shaping their current discourse of resilience and new beginnings. The logo shows a family, intact and holding hands, walking upright into an unknown future. The fading color of their path symbolizes traversing a dangerous liminal state as they leave their family homes, stripped of their national identity. The sun behind them sets over their homeland. But they move forward, and COSL tells the world of their past and present, as well as their hopes and plans for the future.

Multigenerational Families Maintain Dynamic Folklife Traditions

Two common assumptions about refugee populations, that families have been fractured and cultural traditions abandoned, do not hold for this diasporic community. Unlike other displaced groups, Bhutanese families remained largely intact throughout dislocation and ultimate resettlement. In Pittsburgh, we note that families of three generations are common: Parents in their mid-50s through 70s, children in their 30s through 40s, and grandchildren who are of school age through young adulthood. The eldest generation usually has limited reading and writing skills, having grown up in farming communities with limited access to formal education. They are generally the parents of large families, with five or more children constituting the second generation. This middle generation of parents may not have attended school for very long, or at all, because of the difficulties of attending sparsely located schools in the mountains of Bhutan.

The third generation, who comprise the membership of COSL, has more formal educational attainment than their parents and grandparents; having been born in Nepalese refugee camps, they had greater access to the NGO-sponsored schools that grew up over the decades there. Their numbers are significant; approximately 35 percent of Bhutanese refugees were under the age of 18 when resettlement began (Cultural Resource Center 2007). In Pittsburgh, these are the teen and young adult immigrants who have come together to form the core of the COSL community.

Bhutanese refugee youth have some advantages compared with other displaced youth around the world. First, refugees in Nepal have more formal educational resources compared with refugees in other countries. Students usually could attend school in refugee camps through 10th grade, after which they could continue in Nepal’s public schools, an option refugees in other countries do not have (Brown 2001). Additionally, children have rarely been separated from their parents, and heritage traditions including dance, material culture production, and oral storytelling continue.

This is not to say that refugee life is idyllic; conditions in the camps are overcrowded and unsafe, and food and other necessities are scarce. In addition, mental health problems were as great a concern as physical health challenges (Preiss 2013). Today, residual mental health issues are still a concern, one that COSL refers to other refugee-led organizations in the area. Reclaiming their cultural traditions as they find new folk groups to join and contribute to helps this Generation 1.5 exercise a sense of agency and voice. They are the ones actively seeking–and contributing to— safe, welcoming communities in their new cities.

These youthful newcomers have many proficiencies that have helped COSL grow since its founding in 2013 (personal communication with COSL founder Diwas Timsina). They derive resilience and an optimistic stance because of their prior experiences with successfully navigating transnational educational systems, their ability to incorporate new languages (including initial exposure to English in the camps), and their youthful recognition that return to Bhutan will not be likely (Timsina 2016). These features of camp folklife have proven pivotal in Bhutanese young adults’ capacity and desire to continue to generate resources that will enable them and their families to navigate resettlement best in their long-term new home.

As a collective effort, COSL provides multimedia educational and advocacy resources that span a great range of cultural forms of expression. The authors maintain and participate in traditions of their elders, including dance and dress. They also engage in modes of creative expression in their second language of English, including poetry and drama, along with formal public speaking and social media posts. In fusing old traditions and new modes of expression, COSL speaks to the challenges of negotiating belonging as newcomers, whether in classrooms or communities. Some examples of their work, shared below, reflect their dynamic folklife traditions–their ways of knowing, forms of expression, and means of maintaining communal life and rituals in that productive, liminal space between two countries and cultures.

Creative Forums Display Community Cultural Wealth

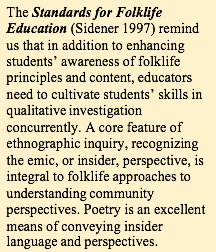

Immigrants, particularly refugees, are too often stereotyped into two broad categories: drains upon the economy whose numbers flood countries of resettlement, or tragic figures who need to be rescued. All too frequently in classrooms and curricula, their voices are silenced or marginalized (Hogg 2011). Folklife programs provide an effective counterpoint to these trends, spotlighting firsthand accounts and perspectives and adding them to the public discourse available far and wide via the Internet. There is much that we could still do to bring lessons from folklife studies into mainstream classrooms. Bowman (2006) notes that folklore and education share considerable common ground and there are several entry points where each could build upon shared pedagogical goals and priorities. She models a multivocal account of best practices that illustrates practical ways to establish mutually advantageous programs, noting the cumulative benefits of applying folklore’s higher order thinking skills to social justice topics. If young people study insider and outsider points of view, position themselves in observing and writing, employ ethical documentation practices, categorize findings, and generate presentations of their ethnographic explorations, they have a leg up on making sense of the world, understanding what it is to be human, and participating in a civil society (77). COSL authors have adopted a similar range of strategies to foreground their collective experiences, their feelings about those experiences, and the consequences for their full membership in communities well-known as well as new.

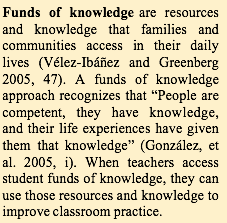

Folklife studies spotlight the dynamic interplay of multiple cultural and political forces in shaping and reshaping the expressive cultures of interacting groups. In this, they share with a wealth-based framework (Yosso 2005) a concern for the ways that folk groups’ community wisdom fosters resilience. Youth gain applied wisdom from the funds of knowledge and expressive traditions in which they grow up. Educators gain better understanding of their students and enhanced pedagogical strategies by accessing student funds of knowledge, which in turn can counter the deficit approaches that remain dominant in educational settings (Hogg 2011).

Folklife studies spotlight the dynamic interplay of multiple cultural and political forces in shaping and reshaping the expressive cultures of interacting groups. In this, they share with a wealth-based framework (Yosso 2005) a concern for the ways that folk groups’ community wisdom fosters resilience. Youth gain applied wisdom from the funds of knowledge and expressive traditions in which they grow up. Educators gain better understanding of their students and enhanced pedagogical strategies by accessing student funds of knowledge, which in turn can counter the deficit approaches that remain dominant in educational settings (Hogg 2011).

What does this look like in practice? González, Moll, and Amanti (2005) argue for teachers to engage directly with students’ home communities through interviews and participant observation. This type of engagement is not always possible; for some families, it may not be desirable. However, in this age of multimedia, entering student spaces includes entering cyberspace. On websites and social media, participants often demonstrate their funds of knowledge in various creative ways, including written, spoken, and visual performance. Such is the case with the Children of Shangri-Lost, whose vibrant web presence is a gateway to their daily lives and funds of knowledge.

In direct response to public discourses that discount their creative voices, Children of Shangri-Lost promote poetry and drama as two prominent forms of artistic expression. Calls for postings and peer “likes” on their social media pages help youth develop and exercise a distinctive, legitimate voice in recasting this simplistic but pervasive narrative. The poem “Unexpected Journey” by Roshna reprinted below, is one such work that expresses the hopes and fears of many youth who arrive with their families. She complicates one- dimensional narratives with her poem, which exemplifies Yosso’s (2005) framework of community cultural wealth.

In direct response to public discourses that discount their creative voices, Children of Shangri-Lost promote poetry and drama as two prominent forms of artistic expression. Calls for postings and peer “likes” on their social media pages help youth develop and exercise a distinctive, legitimate voice in recasting this simplistic but pervasive narrative. The poem “Unexpected Journey” by Roshna reprinted below, is one such work that expresses the hopes and fears of many youth who arrive with their families. She complicates one- dimensional narratives with her poem, which exemplifies Yosso’s (2005) framework of community cultural wealth.

Through their website, social media pages, and public engagements, COSL participants engage in “counter- storytelling,” which Solórzano and Yosso (2002) define much like folklorists describe their intentional scholarly practice, as an interactive, mutually constituting “method of telling the stories of those people whose experiences are not often told (including those on the margins of society). The counter-story is also a tool for exposing, analyzing, and challenging the majoritarian stories of racial privilege. Counter-stories can shatter complacency, challenge the dominant discourse on race, and further the struggle for racial reform” (32). By highlighting their own experiences, on their own terms and in a hybrid language, rather than simply responding to normative mainstream ideas of who they might be or how they ought to fit in, COSL teen poets and writers author their own narratives of how they come of age at the same time they come to understand themselves as nested within, that is, belonging to, many communities at once. As a public website where Bhutanese teens and young adults can freely share their thoughts, COSL’s homepage directly links educators, community service providers, and, importantly, other youth to concrete instances of this alternate view of a newcomer community as bringing something of value to the table.

Shifting to the concept of community cultural wealth also helps move the academic discourse beyond definitions of “social” or “human” capital in the U.S. as primarily those things that can be measured by financial gain or income level, as well as reifying transactional views of success as using others in a network to get ahead, to get access to resources, and to attain “success.” Roshna’s poem expresses how funds of knowledge generate “wealth” and challenges instrumental mainstream views of what constitutes success.

Unexpected Journey by Roshna

Bags packed, rooms left bare,

My Family and I leave with a long stare.

Thinking about my new lifestyle, I begin to worry for a while.

It may be a wonderful change, Although, it could be quite strange.

I think about my friends I’ve left behind, In hope of meeting others so kind,

I shall cherish the memories we made, Which shall never fade.

They say America is a Land of Opportunity, With its people come to unity.

Moving may allow me to see different places, Along with new faces.

It may be a great country at times. But does have some negative signs. My parents are concerned about jobs available,

Some might not be so favorable.

Cost is also a problem, Sinking many families to the bottom.

America has its difficulties,

Though its people are the first of its priorities.

Classroom Application: Learning through Newcomer Poetry

“Unexpected Journey” lyrically expresses 14-year-old Roshna’s hopes and abilities. Educators could also use the poem, with the lens provided by Yosso, to unpack how Roshna has brought along forms of community cultural wealth. Starting with the second line, Roshna expresses familial community cultural wealth with the first of three references to her family. She is saying goodbye and leaving with her family, a source of continuity in a precarious environment. Roshna’s poem speaks to the complex nature of resettlement, noting that it is not all positive (her parents are “concerned”) and finances create serious challenges. Folklife resources that candidly acknowledge complex social issues and conflicted personal desires, not superficially focusing on only happy times, are all the more valuable for their honest poignancy. COSL authors have to figure out where they stand and need to go out into their communities as reporters and social scientists to write their pieces.

She speaks of loss and gain in what Yosso terms social wealth, noting the friends she leaves behind but remaining hopeful about those whom she may meet. Her young voice thus reflects a shared teenage fear of rejection and desire to make new friendships and connections. She honors the extended set of relations and neighbors who have made the move with her family, noting that that they derive a sense of strength from the Pittsburgh Bhutanese’s overall close- knit identity and cultural continuity.

Teachers can capitalize on this expanded sense of the communities to which she has belonged and prompt classroom conversations about students’ diverse types of families and social support networks.

Implicit in Roshna’s depictions of relationships with family and friends is her aspirational wealth, insights that resonate fully with Yosso. She has hopes for the future despite obstacles. COSL websites and programs provide a means for these transitional generations to fall back on the folklore that their parents and grandparents brought with them, particularly the recurring narrative of making a better future for themselves in a new place. COSL posts contribute to an alternate public discourse about newcomers as intact and rebounding ethnic communities. We note that the poem provides the impetus for discussing what it means to develop a transcultural (Suarez-Orozco and Suarez-Orozco 2001) or integrated (Berry 1997; Berry, et al. 2006) identity that honors and continues the folklife of one’s elders while also selectively adopting elements of the new home.

Implicit in Roshna’s depictions of relationships with family and friends is her aspirational wealth, insights that resonate fully with Yosso. She has hopes for the future despite obstacles. COSL websites and programs provide a means for these transitional generations to fall back on the folklore that their parents and grandparents brought with them, particularly the recurring narrative of making a better future for themselves in a new place. COSL posts contribute to an alternate public discourse about newcomers as intact and rebounding ethnic communities. We note that the poem provides the impetus for discussing what it means to develop a transcultural (Suarez-Orozco and Suarez-Orozco 2001) or integrated (Berry 1997; Berry, et al. 2006) identity that honors and continues the folklife of one’s elders while also selectively adopting elements of the new home.

Yosso’s navigational wealth is also at the heart of Roshna’s compelling story, exemplifying how she and her family will locate a place to belong in a “quite strange” place. Because the poem ends on an optimistic note, with a culturally congruent emphasis on people as a high priority, the implication is that her family will indeed steer a course among the new terrain with success, if not ease. Educators can also look to the poem for larger social issues, for example, the meaning of success, including the relative value of individualistic gains and the merits of community uplift and collective accomplishments.

In the act of writing and publishing her poem, Roshna also demonstrates linguistic community cultural wealth. She is not only multilingual in the most literal sense of speaking more than one language, she can also express herself in multiple genres, including poetry. Over the years, we have repeatedly been struck that this skill is particularly pronounced among these youth, who as the in-between generation become translators for their families. This role, better described as cultural brokering (Piper 2002, 88), involves not only direct language translation but also facilitating family involvement with individuals, organizations, and institutions in the new homeland.

Finally, one may read in the poem a subtle expression of resistance: She is hopeful for her new life in America but knows that it will have its “difficulties” and those challenges will be devastating for some (“sinking many families to the bottom”). This last form of resistance, a willingness to name social problems and inequities, is characteristic of many who post to COSL’s website. Roshna’s rendering of her family’s “Unexpected Journey” is both poignant and provocative. It provides an educational resource that their peers, teachers, social workers, and local politicians would do well to “unpack” using these core principals of cultural wealth and assets brought by newcomers.

In summary, the dynamic social media and information websites curated by COSL youth spotlight their living folklore that counters others’ typical frozen-in-time or romanticized discourses about them. By composing and sharing elements for peer review that employ hybrid forms of literacy (for example, poetry, prose, and traditional epic storytelling genres), they provide rich, multilayered accounts for their community, the wider communities within which they live, as well as diasporic Bhutanese around the world who can log in and follow them. Whether collectively gathered composite stories, recounting others’ adventures, or forms of individual witnessing (such as Roshna’s poem), all are brave acts of counter-storytelling, which Solórzano and Yosso (2002) note serve at least four functions:

They can build community among those at the margins of society by putting a human and familiar face to educational theory and practice, (2) they can challenge the perceived wisdom of those at society’s center by providing a context to understand and transform established belief systems, (3) they can open new windows into the reality of those at the margins by showing possibilities beyond those they live and demonstrating that they are not alone in their position, and (4) they can teach others that by combining elements from both the story and the current reality, one can construct another world that is richer than either the story or the reality. (36)

COSL is a folklife organization that both in its process and product can serve as a role model for other social justice organizations.

For these reasons, we believe that folklife educators would particularly appreciate the COSL contributions to providing accessible and age-appropriate primary documents authored by other teens and young adults. By supplementing required texts–or replacing them altogether–with first- person narratives, we believe teachers can counter strategic silences about newcomers typical of most current curricula. Encouraging (non-immigrant) students to interview their relatives about their families’ stories of movement, migration, and integration can help students make bridging connections between generations and cultural groups. Such stories provide peer-initiated prompts to foster “tough conversations” that dovetail well with the nearly ubiquitous anti-bullying programs in schools. Teachers can also contrast Roshna’s language with newspaper or online accounts that emphasize newcomers as sources of risk, danger, threat, or demise; often having contrasting examples enables students to see commonplace labels as pejorative and replaceable rather than simply what has been accepted as normative. Finally, students and teachers can look to Roshna and other COSL participants’ use of multiple genres for inspiration to articulate their own and their families’ funds of knowledge.

Outreach Activities Bridge Newcomer and Host Communities

In addition to highlighting explicitly the substantial forms of community cultural wealth that Bhutanese can contribute to their host communities, COSL forums provide the means for building effective linkages between social groups. In a nation, and in particular an urban environment such as Pittsburgh where housing segregation by race and social class leads to increasingly isolated, mono-cultural neighborhood schools and churches, teachers need to seek out allies, especially boundary-crossing, even transgressing, institutions such as COSL.

In his analysis of shifting communal relationships in the U.S., Putnam (2000) discusses two forms that social networks can take: bonding and bridging. While bonding serves the essential purpose of enhancing intra-group coherence and cohesion, bridging creates intentional connections between one’s home group and external organizations and institutions. Bonding and bridging are both important for immigrant acculturation, regardless of generation. COSL, in their mission, alludes to bonding and bridging networks:

Our mission is to raise awareness and to educate people about the history and challenges faced by the refugee and immigrant population through short films and blog posts. We hope to engage youth in community issues and programs as well as inform the public about the experiences of refugee and immigrant communities [emphasis added]. (COSL website 2017)

Here they note their efforts to bridge their community with others. They also reference the two- way nature bridging social networks should take in their efforts to engage Bhutanese youth in community issues, including home and host communities. Specific examples of the former include intergenerational programming with Bhutanese elders, who help COSL participants maintain home culture practices (such as language, religion, music) that could fade over time. Engagement with host community institutions includes college visits and inviting American friends and neighbors to understand and participate in Bhutanese community festivals. Outreach and advocacy have taken on many forms.

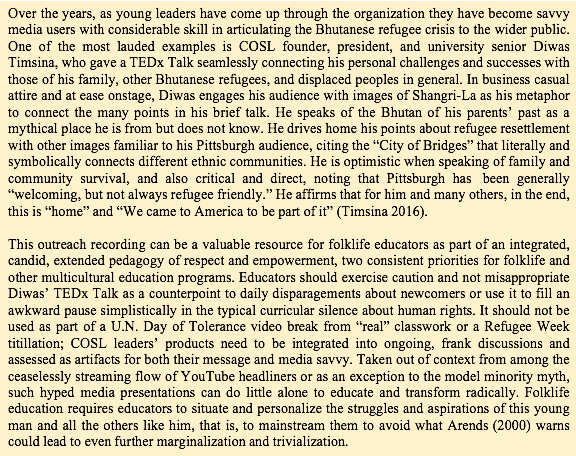

Folklife, while experienced within a specific community, is lived out by one particular person, his story combining with others’. Thus, from the audience’s perspective, hearing individualized accounts is important. On the speakers’ side, learning to articulate their stories and worldviews to the larger public is an essential prerequisite. In this TEDx Talk, Diwas Timsina’s poised stage presence among other experts counters typical depictions of those who are frequently “Other-ed”; this is an important message to educators and other advocates. It opens the door for critical conversations about race, identity, and citizenship.

High-profile online talks like TEDx have been a pleasant extension of the core business of COSL, which is local, in-person programming. Because COSL is concentrated in a small set of Pittsburgh neighborhoods and its members span artificial age and geographic constraints, they can offer programming collectively that fills the need for ongoing presentations in many different school districts and community centers. COSL often engages in creative programming to highlight folklife traditions that they literally brought along with them: their regalia, traditional dances, and styles of storytelling.

High-profile online talks like TEDx have been a pleasant extension of the core business of COSL, which is local, in-person programming. Because COSL is concentrated in a small set of Pittsburgh neighborhoods and its members span artificial age and geographic constraints, they can offer programming collectively that fills the need for ongoing presentations in many different school districts and community centers. COSL often engages in creative programming to highlight folklife traditions that they literally brought along with them: their regalia, traditional dances, and styles of storytelling.

Folklife education contributes the message that all cultures both draw inspiration from their expressive traditions as well as innovate new content, forms, and media (both tactile and virtual). A pioneering COSL program illustrates these experimental and improvisational dimensions. The “Showcase of Bhutanese Culture: Featuring Song, Dance, and Poetry” used several art forms to share their folklife traditions in a new American setting. In this showcase, COSL participants shared their history through a brief play by one of their members about the history of the Lhotsampas and their expulsion from Bhutan. The play ended on a note of hope, with actors preparing to move from a refugee camp to the U.S. (“Showcase of Bhutanese Culture…”). At this and other events, Bhutanese music and dance feature prominently. By reaffirming heritage stories and modes of storytelling, reusing material cultural artifacts, and reinterpreting them for new audiences, these performances keep those folklife traditions dynamically alive. We also saw COSL live up to this larger mission of building bridges that facilitate an enhanced, two-way traffic in ideas at a panel, “Come Talk to Me.” As its title suggests, COSL panelists literally invite outside community members to join them and learn about Bhutanese refugees in a relaxed, friendly environment at the local library. These open panels, which they plan to repeat periodically, offer people of all walks of life the opportunity to learn about diverse folklife expressions right in their own neighborhood.

These high-energy events starring local people can indeed provide an excuse to gather the community for reciprocal advantage. Past research with youth-centered festivals (Porter 2000) has led us to continue to investigate the mutual benefits that can accrue when adults step back and support youth in designing, producing, and hosting complex performances of cultural competence. These playful, amateur events require a team effort and thus can help often socially isolated refugee youth extend their networks and social ties across lines of gender, generations, and geography. COSL has wisely continued to foreground the meaningful, versus superficial, contributions and leadership of young adults strategically within the community. Events presented to mixed insider and outsider audiences bring attention to teens’ valued traits and skills. These events can reveal another side not always apparent in the classroom, so their teachers would do well to attend such folk group-initiated forums. Having an appreciative audience who recognizes their expertise and skill can be very valuable for those who go through the effort to put on such a production. The attention provides impetus to remain authentic and relevant, reinvent folklife traditions, and “link the past, present, and future in tangible ways…offer[ing] participants an annual opportunity to reinvent their homeplace, to create an amalgam of preindustrial and postmodern, core and peripheral, traditional and avant-garde” (Porter 2000, 210). The results, for newcomers as well as longer-term residents, are enhanced senses of place, self, and of shared community.

Learning what makes their folk group distinctive and worth celebrating contributes to Giroux’s pedagogical project of difference, in which students “engage the richness of their communities and histories while struggling against structures of domination.” In public venues such as COSL’s folklife festivals, they play with different, often hybrid, forms of literacy and performance, learning adeptly to “move in and out of different cultures, so as to appreciate and appropriate codes and vocabularies of diverse cultural traditions in order to further expand the knowledge, skills, and insights that will need to define and shape, rather than merely serve, in the modern world” (Giroux 1992, 246).

In our work with COSL, we are able to enter into informal, ongoing conversations about the nature of cultural exhibits and norms of public performance and display. With Hogg (2011), we continue to ask questions to drive funds of knowledge scholarship and praxis forward: Which forms of heritage knowledge are most salient and relevant to the youthful Generation 1.5 when they choose which elements to showcase? Which pedagogies that are effective, embodied ways of knowing used across generations within the group could also be incorporated into diversified classroom pedagogies that would successfully engage this group as well as many learners? Which elements of folklife are highly significant to this group because they have a recent history of migration, but may not be as important to groups still in refugee camps? How can COSL continue to showcase their funds of knowledge well into students’ middle and high school years, instead of the current practice of concentrating offerings in the elementary school years? These are great questions for young adult event planners to consider carefully; they are also directly applicable to teachers who are considering inviting local tradition bearers to do workshops in their classes or are designing a school-community multicultural night. Hogg asserts that acknowledging local newcomers’ living folklife expertise and incorporating their funds of knowledge into classes could lead to greater “relevance and authenticity of schooling” as well as enhancing Bhutanese immigrant “community empowerment and transformation” (2011, 673).

A final comment about the multimedia aspects of COSL’s work is in order. Above and beyond the actual running time for these events, the collectively curated COSL website provides a transcendent “place” outside time or space to replay photos and videos. These interactive archives further expand the range of opportunities and audiences who can interact, share insights, and introduce themselves to one another. Selective representations of the 2015 Bhutanese Showcase provide a second pass for COSL members to learn critical folklife curation skills. Learning which elements to record ethnographically helps them hone foundational fieldwork proficiencies. Writing the synthesis captions, interpreting selected photos, and labeling people and food all are visual literacy competencies they gain. Explicitly naming allies and local supportive political figures (see photo caption below) further enhance their social standing and show their expanding alliances and social networks. They validate group-based expressions of “success” in the “American Dream.” The website also offers means for the youth to explore transcultural norms of politeness and personal expression, not the least of which is publicly stating gratitude for sponsorship, audience attendance, and skilled performances by peers.

The public “thank-you note” function of the website is also a good model for classroom teachers, as they could encourage young hosts who receive folklife tradition bearers as guests and visitors to verbalize appreciation and acknowledge, and thus honor, the gifts that they have shared. Too often this practice falls by the wayside in the early elementary years. However, teens are just as much in need of teachers’ prompts to articulate and express their gratitude to role models in their community who generously share their talents.

In summary, behind diversified COSL events and programs is the message that ours is a vibrant, interesting culture with art forms that we are justifiably proud of and intend to continue. Recitals showcase these teens and young adults not as relatively silent classmates, but as choreographers of their futures. The events that COSL members create and deliver, and then continue to reinterpret and critique online, serve as exemplary practices for multilayered educative experiences for youth and their advocates.

Sharing the Wealth of Folklore-Based Curricula: How Educators Can Bridge Cultural and Civic Gaps

Through their vibrant civic folklife organization CSOL, Bhutanese newcomers offer a dynamic set of public platforms for expanding the impact of their poetic voices and cherished cultural practices. Their advocacy, outreach, and media innovations provide significant resources for their resettled families, their new neighborhoods and schools in Pittsburgh, and their worldwide diasporic community. The young adults of Generation 1.5 have made strategic use of COSL to showcase the many forms of cultural wealth that they have inherited and are actively generating in their new country. Schools and community organizations could adopt some of COSL’s approaches in the classroom, using the growing online resources to inspire and model creative forums led by and not just about newcomers.

These are ready material to incorporate into ongoing, educative dialogues about belonging, otherness, and representation. COSL members’ commitments to offering community events, and linking these with intercultural dialogue and critique, provide further impetus for what could become transformative community encounters. By welcoming their Pittsburgh neighbors to folklife festivals and panels, they are paving the way for substantial bridges that will facilitate continued, two-way flows of information. In this fashion, we believe that COSL’s advocacy and dynamic, multimedia platforms provide important schoolroom and community assets. Indeed, we believe with Masney and Ghahremani-Ghajar (1999) that respectfully validating differences within the core curriculum, not as a tangent or exception, is a prerequisite for a more inclusive school culture overall. We believe that incorporating folklife-oriented collaborations with newcomer groups will directly contribute to an enhanced school culture that is more welcoming and respectful.

By looking at folklife as arising out of–and in turn contributing to–community cultural wealth, we can see the resources that newcomer communities can contribute uniquely to a more inclusive U.S. civic life. With coursework and activities that draw on a perspective of community cultural wealth, as opposed to newcomers’ “lack of” resources, educators can draw out lessons about the distinctive, as well as common, experiences of newcomers who seek a place to belong and wish to define “success” on their and their families’ terms. Sometimes those newly introduced to “The American Dream” are most able to articulate its rewards and inconsistencies most poignantly, as Diwas did in his TEDx Talk. Success can certainly include leading feasts, fairs, or festivals. These help youth put their community into perspective as well as envision the kind of community they would like to belong to in the future (Porter 2000). Finding such safe spaces to belong and thrive is a critical aspect of cultivating a resilient transcultural identity in a new place (Suarez-Orozco and Suarez-Orozco 2001).

In conclusion, Hamer notes that folklife education can directly and substantially contribute to the project of critical emancipatory multiculturalism originated by McCarthy (1994). Hamer identifies five “themes and purposes” in folklife education that we also see directly represented in COSL products:

(1) valuing nonprofessional, everyday artistic expressions; (2) instilling local and family pride; (3) challenging the authority of elite and popular culture; (4) recognizing “indigenous teachers” as authoritative (i.e., recentering authority outside institutions); and (5) promoting collaborative action within classrooms and extending outside of schools. (2000, 56)

COSL shows us that these themes can come alive in both form and content; the medium is also part of the message. For instance, ESL and other classroom teachers can use COSL’s archived narratives and performances to engage worldwide audiences. Further, using a folklife lens that affirms and honors forms of cultural expressions tied to embodied ways of knowing, such as through dancing, singing, or eating together, benefits the holistic curriculum. Hamer’s five themes dovetail with our assertion that COSL advocacy and direct community outreach are effective modes of folklife education that can bring more voices into the mainstream and thus contribute to the sense of being legitimate, productive community members.

The public website provides a particularly helpful medium to share Generation 1.5’s experiences, now including issues that concern them as they transition from K-12 to higher education. For this generation in particular, cyberspace is an important space for having their unfiltered voices heard. They construct new knowledge, seamlessly remarking on all kinds of topics and genres. Both producers and consumers are hungry to use novel media, and perhaps being online in visually appealing bursts can help capture the attention of students today; folklife teachers will have to report back on how well their students respond to these kinds of peer-generated multimedia modes of storytelling.

COSL members’ eclectic commentaries on folk, popular, and elite cultural forces and artists further trouble simplistic notions, or rankings, of these forms of cultural expression. Folklife- inspired educators can build on this principle of inclusive, nonhierarchical approaches to what counts as “culture” and encourage students to look to tradition bearers in their personal circles as well as on the public stage. In summary, we also encourage teachers to look beyond the bounds of the classroom or school day to acknowledge the allies and tradition bearers who can help identify and work on sociocultural issues of shared concern.

In Pittsburgh, T-shirts and store placards that proclaim “Build Bridges Not Walls” have proliferated since the November 2016 election. The lesson of cross-cultural bridging–and the emphasis on the two-way nature of that bridging–is critically important. This is a message that educators would do well to adopt as a core lesson: It is not about the Bhutanese fitting into a predetermined slot in American mainstream culture; rather, it is about contributing to a reciprocal civic interchange in which all community members can, and need to, participate. It is about mutuality, versus perpetuating an “us-them” orientation to immigration.

This is a timeless lesson for a nation of immigrants. Teachers can use these COSL-led events to update and expand the U.S. American mythos of being a “Country of Immigrants” with much in common, as well as many divergent group histories. A wonderful tie-in would be comparing and contrasting local Bhutanese stories with materials available through the Tenement Museum in New York City. We especially recommend their movie, An American Story, about immigration as something that has personally shaped waves of ethnic groups as well as the nation. Educators interested in museology would also appreciate the explicit mention of how the museum pursues its mission.

Folklife studies are about meeting the Other where they are, at the juncture of what has been and what could yet be. And, as Children of Shangri-Lost poignantly tell themselves and us, we are all “other” at some point and need one another to reframe a collective future. Folklife education that makes critical, ongoing use of divergent forms of storytelling and visual literacy gives us more tools to integrate primary resources into our curricula. Educators who recognize and respect community partners’ expertise are more effective collaborators who have a stake in shared success. By wholeheartedly listening to one another, reading and responding to diverse blogs and photos, and celebrating each of our distinctive contributions within our classrooms, we proactively create school cultures where we all have a voice, feel like we belong, and can thrive.

Maureen K. Porter is an Associate Professor at the University of Pittsburgh and the Associate Director of the Institute for International Studies in Education. Her work as an engaged scholar in the field of anthropology and education has most recently been enhanced through serving as Program Director of the Fulbright Hays Group Project Abroad on Ethiopian Indigenous Wisdom and Culture. Susan Dawkins is a doctoral candidate in Social and Comparative Analysis in Education at the University of Pittsburgh and a reading instructor at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Her dissertation research, inspired by her interactions with local refugee communities, is on acculturation processes of Generation 1.5 refugee youth.

URL

Children of Shangri-Lost http://www.shangri-lost.org

Works Cited

An American Story. nd. New York: Lower East Side Tenement Museum. DVD, 30 min. Arends, Richard I. 2000. Learning to Teach. 5th ed. Dubuque: McGraw-Hill.

Berry, John W. 1997. “Immigration, Acculturation, and Adaptation.” Applied Psychology: An International Review, 46.1: 5–34.

Berry, John W., Jean S. Phinney, David L. Sam, and Paul Vedder. 2006. “Immigrant Youth: Acculturation, Identity, and Adaptation.” Applied Psychology. 55.3: 303–332. doi:10.1111/j.14640597.2006.00256.x.

“Bhutanese Refugees Find Home in America.” 2016. White House Archives, March 11, accessed April 1, 2017, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2016/03/11/bhutanese-refugees-find-home-America.

Bowman, Paddy B. 2006. “Standing at the Crossroads of Folklore and Education.” The Journal of American Folklore. 119.471: 66-79.

Brown, Timothy. 2001. “Improving Quality and Attainment in Refugee Schools: The Case of the Bhutanese Refugees in Nepal,” in Learning for a Future: Refugee Education in Developing Countries, eds. Jeff Crisp, Christopher Talbot, and Daiana Cipollone, 109–161. Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees.

Children of Shangri-Lost. 2017. http://www.shangri-lost.org.

Cultural Orientation Resource Center. 2007. “Bhutanese Refugees in Nepal.” CORC Center Refugee Backgrounder No. 4. http://www.culturalorientation.net/learning/populations/bhutanese.

Erel, Umut. 2010. “Migrating Cultural Capital: Bourdieu in Migration Studies.” Sociology. 44.4: 642-660. Giroux, Henry A. 1992. Border Crossings: Cultural Workers and the Politics of Education. New York: Routledge.

González, Norma, Luis C. Moll, and Cathy Amanti, eds. 2005. Funds of Knowledge: Theorizing Practices in Households, Communities, and Classrooms. New York: Routledge.

Hamer, Lynne. 2000. “Folklore in Schools and Multicultural Education: Toward Institutionalizing Noninstitutional Knowledge.” The Journal of American Folklore. 113.447: 44-69.

Hogg, Linda. 2011. “Funds of Knowledge: An Investigation of Coherence Within the Literature.” Teaching and Teacher Education. 27: 666-677.

Hutt, Michael. 2003. Unbecoming Citizens: Culture, Nationhood, and the Flight of Refugees from Bhutan. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lower East Side Tenement Museum. 2017, http://tenement.org.

Masney, Diana and Sue-San Ghahremani-Ghajar. 1999. “Weaving Multiple Literacies: Somali Children and Their Teachers in the Context of School Culture.” Language, Culture and Curriculum. 12.1: 72-93.

McCarthy, Cameron. 1994. “Multicultural Discourses and Curriculum Reform: A Critical Perspective.” Educational Theory. 4: 81-98.

Meyer, Calvin F and Elizabeth Kelley Rhoades. 2006. “Multiculturalism: Beyond Food, Festival, Folklore, and Fashion.” Kappa Delta Pi Record. 42.2: 82-87.

Pipher, Mary. 2002. The Middle of Everywhere: The World’s Refugees Come to Our Town. New York: Harcourt.

Porter, Maureen K. 2000. Integrating Resilient Youth into Strong Communities through Festivals, Fairs, and Feasts, in Developing Competent Youth and Strong Communities through After-School Programming, eds. Steven J. Danish and Thomas P. Gullotta. Washington, DC: Child Welfare League of America Press, 183-216.

Preiss, Danielle. 2016. “As Bhutanese Refugee Camps in Nepal Wind Down, Resettlement Program is Considered a Success.” PRI Public Radio International, December 28, accessed April 27, 2017, https://www.pri.org/stories/2016-12-28/bhutanese-refugee-camps-nepal-wind-down-resettlement-program-considered-success.

— . 2013 “Bhutanese Refugees Are Killing Themselves at an Astonishing Rate.” The Atlantic. April 13. Putnam, Robert. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Rizal, Dhurba. 2004 “The Unknown Refugee Crisis: Expulsion of the Ethnic Lhotsampa from Bhutan. Asian Ethnicity. 5: 151-177.

“Showcase of Bhutanese Culture: Featuring Song, Dance, and Poetry.” City of Asylum, July 5, 2016, http://cityofasylum.org/events/category/family/2016-07-05

Sidener, Diane. ed. 1997. Standards for Folklife Education: Integrating Language Arts, Social Studies, Arts and Science through Student Traditions and Culture. Immaculata, PA: Pennsylvania Folklife Education Committee.

Solorzano, Daniel G. and Tara J. Yosso. 2002. “A Critical Race Counterstory of Race, Racism, and Affirmative Action.” Equity & Excellence in Education. 35.2: 155-169.

Suarez-Orozco, Carola and Marcelo M. Suarez-Orozco. 2001. Children of Immigration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Timsina, Diwas. “Finding a Home in Search of Shangri-La.” TEDx Pittsburgh., 9:20. May 2016, http://www.shangri-lost.org/2016/06/finding-a-home-in-search-of-shangri-la-diwas-timsina.

Vélez-Ibáñez, Carlos and James Greenberg. 2005. “Formation and Transformation of Funds of Knowledge. Funds of Knowledge: Theorizing Practices in Households, Communities, and Classrooms. New York: Routledge, 47-70.

Yosso, Tara. 2005. “Whose Culture Has Capital? A Critical Race Theory Discussion of Community Cultural Wealth.” Race, Ethnicity, and Education. 8: 69-91.

Zeppa, Jamie. 1999. Beyond the Sky and the Earth: A Journey into Bhutan. New York: Penguin Publishing Group.