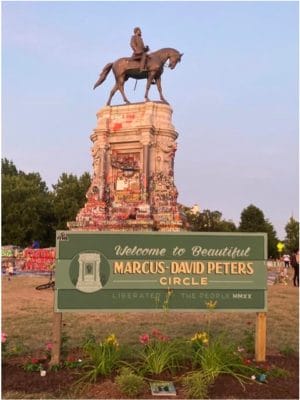

Marcus-David Peters memorial at the Lee Statue in Richmond, Virginia. All photos courtesy of the author.

In this article, I reflect on ways that my folklore-studies approach to the college writing classroom enables Virginia Commonwealth University’s diverse student population, and especially historically marginalized groups, to create and appreciate cultural texts. In particular, I illustrate how a “material culture” course theme can convey the importance of folklore in the writing classroom as a tool to explore locally engaged and community-driven topics. My examples include racial and social justice, gentrification, and environmental and cultural sustainability to help students practice college-level research and writing skills. I argue that this is especially useful as students make sense of the 2020 pandemic and Black Lives Matter protests that deeply affected their connection to the VCU campus (and to Richmond city) and their emotional wellbeing. I share several pedagogical tools and discuss the role that each plays in the organization of my material culture course to engage students in analyzing, evaluating, and creating both written and digital texts.

Given VCU’s diverse student population, and especially Richmond’s problematic legacy of enslavement and white supremacy, a focus on material culture can become a powerful writing tool to help marginalized students find their voice and speak up against past and present injustices within the Commonwealth. In turn, such pedagogical practices can help us folklore-trained instructors practice decolonizing the college writing classroom.

Pedagogical Framework

VCU’s focus on community-engaged teaching and learning reflects a larger trend within both folklore studies and education.1 VCU’s Focused Inquiry Program, which I joined in the fall of 2017, brings together faculty from a variety of disciplines and offers seminar-style classes for first- and second-year students as part of the core curriculum. The program’s mission is “to foster curiosity about the world at large through inquiry-based, community-engaged, and experiential learning” (Department of Focused Inquiry). Here I draw on my experience in the classroom as well as pedagogical resources that I have created or adapted for my students, particularly within the context of the 2020 pandemic and BLM protests.2 I have structured this article according to the basic principles of most academic writing courses: textual analysis, research, and writing.

As early as 1975, Andrew Badger encouraged college instructors to adopt the use of folklore in writing classes, as “folklore is a source for writing which will involve the student in doing what all honest writers do—that is, write something which they know about to an audience which actually exists” (288). However, writing in 2014, Jennifer Curtis reminds us how the value of students’ homegrown knowledge is still dismissed in formal education, especially when it comes to non-dominant groups. Moreover, she observes how “…interdisciplinary information may be limited by discipline boundaries or discipline-specific conferences and journals where the results are not generally known within the field of composition, especially by first-year teachers” (Curtis). As a folklore-trained writing instructor, then, my goal is to share my teaching experience and resources not only with fellow folklorists who teach writing intensive courses at the college level, but also with fellow writing instructors, hoping to raise awareness about the benefits of folklore studies in the college writing classroom.

In adopting a folklore-studies approach to the teaching of community-driven and locally engaged topics, I am reminded, with Kara Rogers Thomas, how such endeavors “[do] not require folklorists to reinvent themselves and take on new academic identities. The best collaboration allows us to draw deeply from the well of folklore studies” (64). Both the inherent interdisciplinarity of folklore and its attention to the vernacular fit well with the increasingly strong focus on situated knowledge and place-based learning within current college education curricula (Bowman 2004, 385). Indeed, the benefits of a folklore-studies approach to education lie not only in what Paddy Bowman calls “valuing the ordinary,” (2004, 385) but also in the use of ethnographic methodology, which allows for a “close observation, reflection on, and documentation of cultural expressions and processes” (2006, 74).

Textual Analysis: Appreciating Material Culture Texts

A material culture framework naturally lends itself to exploration of place-based and community-engaged topics, especially considering the complex history of Richmond, Virginia, as the former Capital of the Confederacy.3 As the Confederate legacy has been openly questioned in the last few years, and especially during the Summer 2020 BLM protests, the urban structure of Richmond has become a platform from which to observe directly historical events happening both locally and globally. Paddy Bowman and Lisa Rathje (2017) argue that “…folklore-in-education tools make more visible the cultural texts that students know and illuminate how dominant sociocultural narratives work and are perpetuated.” By studying material culture, then, VCU students are able to pay attention to the many cultural texts surrounding them on and off campus and reflect on how these texts reveal larger issues of racial and social injustice.4 My experience sharing these texts so far revealed that most of my students are very familiar with the legacy of enslavement and the Confederacy in Richmond and elsewhere in the United States and that many are personally invested in the BLM cause; however, they are not trained to observe material culture objects closely and use their observations to gain a deeper understanding of those social and racial justice issues. As Anne Pryor and Paddy Bowman remind us, “the field of folklore offers tools, strategies, and resources to help educators understand how culture influences ways of learning…” (2016, 444). My goal, then, is to help students make connections between racial and social justice issues that they are already familiar with and ways that these issues are embedded in the material culture framework of the communities they inhabit.

Find these activities written out as assignment prompts and worksheets in the Classroom Connection pdf.

Find these activities written out as assignment prompts and worksheets in the Classroom Connection pdf.

Material Culture Observation and Interviewing Exercise. Since I joined the Focused Inquiry’s Richmond as Text Faculty Learning Community, I have created or adapted various class assignments that aim at familiarizing students with material culture analysis as a way to explore Richmond’s city space. In preparation, students read and discuss local journalist Michael Paul Williams’ article “We Remain Two Richmonds,” which describes the city as divided into two distinct entities: “Richmond” refers to the city’s historical core, African American cultural heritage, and disenfranchised neighborhoods, while “RVA” refers to the tourist and creative rebranding of the city, which in turn is linked to the current process of (white) gentrification (Williams 2017). Students have also discussed the genesis of the RVA advertising label (RVA Creates) and its white and outsider representation of the city, as well as the more recent BLKRVA initiative, which aims at reclaiming and promoting African American history, culture, and business. With this framework in mind, students are asked to observe their campus/off-campus surroundings in search of elements that could be interpreted as “Richmond,” “RVA,” or “BLKRVA” (or all). As part of their observational tour, students collect and bring to class a material object—a flyer, magazine, menu item, gadget, logo, item of clothing, food item, etc., or a photo of the actual object—as a token of their findings. We use these objects in class to practice linking close observation, interpretation, and hypothesis formulation.

While the Richmond/RVA hypothesis can easily be replaced with a different one, I find the basic structure of this exercise useful in that it allows students to practice close observation and analysis and familiarize themselves with interviewing techniques, which they can implement in research projects later in the semester. The post-interview reflection in particular invites students to assess the quality of their interview questions and ways to improve their interviewing.5 From the perspective of material culture pedagogy, by using their observation findings to formulate hypotheses related to Richmond/RVA/BLKRVA, students can look for direct links between the material objects that they collect and the ideological framework often embedded in those very objects, as historical and current planning visions for the city of Richmond.

Visual Analysis Exercise. Following the summer of 2020, I started to incorporate photo documentation of Richmond’s protests into my class activities on material culture analysis,6 particularly documentation regarding the almost daily changes to the Robert E. Lee Statue on Monument Avenue as protesters inscribed their voices in many media on the statue. One image that I use was taken by the freelance photographer Julia Rendleman for Reuters June 5, 2020, during the height of the protests. It shows two young African American ballerinas, Kennedy George and Ava Holloway, wearing matching black tutus and posing in front of the statue with their fists aloft. This image is particularly useful because it contains elements of both material (statue) and nonmaterial (dance) culture, which helps me reiterate the differences between the two in class, and especially because it offers students an opportunity to reflect both on the statue and on the photo itself.

As they complete this exercise, students reflect on the material culture surrounding Richmond’s protests while practicing visual analysis skills. In doing so, students build observational and analytical skills that they can use later in the semester to explore Richmond’s monuments and other examples of material culture locally or within their own communities. Most student interpretations of the image focus on the ballerinas as “powerful and confident,” “standing tall and proud,” “commanding respect,” “showing strength and resilience,” and illustrating “determination” and “seriousness” through their facial expressions and body positions. Students also note how this feeling of power and resilience is possible through the juxtaposition between the dancers and the monument behind them; for example, “the two dancers can be thought of as contrasting with the graffiti because they represent grace in this image, but they have their fists raised, which has been a symbol of the BLM movement. Their black costumes also contrast with the color of the graffiti which really makes them stand out.” While most students agree that “the two ballerinas are there to show not only their support for their community, but also demonstrating an act of ‘taking back power’ from the spot most African Americans avoided due to its racist history,” several also believe that the image can “represent struggles of female empowerment (especially the empowerment of black women).”7 Therefore, as students formulate their interpretations by attaching a narrative to each object represented in the image, I am reminded by Rossina Liu and Bonnie Sunstein that “writing… gives shape to stories that the artifacts carry and in so doing reshapes the artifacts themselves…Indeed, writing has the power to turn objects into stories and stories into objects” (Liu and Sunstein 2016).

The last set of questions in the exercise focuses on the role of cultural texts, both material and nonmaterial, in helping build individual and collective narratives. I am also asking whether new information retrieved through contextual evidence helped students confirm or challenge initial thoughts about the photo. One student notes how this exercise “gave [her] a clear image on how powerful the photo is to recent news, and how much one photo can have a change on people,” while another writes that “the context confirms [her] original impression of the photo, which was the idea that art can be an incredibly powerful and vital form of protest. The Lee statue couldn’t be torn down, so art was used to overpower it. In a way, the overwhelming amount of pro-BLM and anti-police graffiti, coupled with the two ballerinas giving the black power fist, work to effectively muffle the statue’s message of oppression.”

While focusing mainly on the photo and the material culture represented in it, this exercise is also an opportunity for students to share (in class or as homework) what they already knew about the 2020 protests and how this exercise helped confirm their understanding or rethink the protests from a new perspective. I believe that leaving students free to interpret these cultural texts on their own and offering a space for discussion afterward is especially important when considering the politically charged nature of the protests and their direct impact on the material structure of the VCU campus and of Richmond as a whole. This approach became particularly useful as I strove to keep my classroom an unbiased, safe space in the fall of 2020 leading up to the presidential elections.

Research: Ethnographic Observation within and beyond the Pandemic

A focus on material culture in the first part of the semester enables students to learn first about local culture from the perspective of its tangible objects and then combine their ethnographic findings with bibliographic research in the second part of the semester, as they write their research papers. To that end, I engage students in ethnographic observation through walking or bus tours of the VCU campus as well as class or individual visits to Richmond’s Arts District and mural collection; I also ask students to visit local museum exhibitions and report observations by completing an analysis and reflection exercise.

When the VCU campus shut down on March 16, 2020, my students had just formulated their research projects on Richmond-related topics, such as Black-owned businesses, socially engaged art, Confederate monuments, and African American cemeteries. In our initial Zoom meeting, students were evidently overwhelmed by the sudden changes in their personal and academic lives. Even for those who could continue participating in class discussions and doing classwork (about half the class), their new living situations would make it very difficult to conduct in-depth local research on Richmond, especially firsthand observation. My main goal then was to make sure that all my students, regardless of location and access to technology, could complete coursework. The following assignment reflects my pedagogical challenges at the time and ways that I adjusted my ethnographic approach accordingly.

Neighborhood Observation Tour. Students are asked to tour an area of Richmond that they already know or the neighborhood where they live. In preparation, they have learned about current social justice issues in Richmond and discussed the article “Viewpoint: Walk This Way” (2020), in which the author William Littman reflects on the importance of walking as a strategy for ethnographic observation. Students conduct their own walking tours, take notes and photos of what they observe, reflect on the experience, and present the experience to the class as a PowerPoint/Google Slide presentation8. The main goal is for students to practice ethnographic observation as Littman did in his study and analyze the data that they observe; in doing so, students apply what we learned in class about Richmond to what they observed firsthand, making direct connections between material culture examples surrounding them and the racial and social justice issues that we explored as a class. For example, students identified concrete evidence of VCU’s push for cultural diversity in the area, with “a bunch of local businesses such as the Village Market and Kuba Kuba,” but had to reconcile that discovery with the presence of “larger retail stores […] such as Barnes and Nobles and Kroger,” thereby meaningfully testing VCU’s, and their own, definition of diversity as necessarily more inclusive. This observation tour also gave them an opportunity to expand their definitions of diversity (which for many remained rooted in ethnicity), especially given “the mix of students, well to do and emerging families, a few homeless people within the area.”9 As he walked around the VCU area, another student noted that “as the safety increased the inclusivity dropped,” since he observed the highest safety measures in predominantly white gated areas. This reflection opens the door to thinking more critically about subject position and how a student’s fieldwork observations are influenced by their own cultural identity and cultural knowledge.

Once students share their walking experience in class, we discuss how ethnographic research allows us to draw on various perspectives and combine data from published sources with direct observation. I find this method useful even if students’ chosen research topics are related to other aspects of material culture other than urban landscape.

The 2020 pandemic certainly limited assignment options so I replaced Richmond with students’ own neighborhoods in this assignment. The task of walking rather than taking the bus also seemed like a safer option during a pandemic, although both work to encourage students to look past their perceptions while driving.10 Yet another challenge was that this assignment called for special safety recommendations, described in the lesson plan. Finally, while in previous classes I would ask students to incorporate their ethnographic findings into their final research paper, I decided to grade the ethnographic observation assignment separately to break the course into several short assignments. This option is more likely to help students in distress complete the bulk of the coursework and pass the course.

Shifting the focus to students’ neighborhoods in Richmond or elsewhere worked well for most students, since many had left campus or Richmond altogether and moved home; this ultimately confirmed the benefits of focusing on students’ own “ordinary” or homegrown knowledge as we teach ethnographic research whenever actual local research is not possible. While walking around the town of Sandston, Virginia, where she currently lives, one student noted a clear lack of cultural diversity and healthy food options, limited walking/biking and public transportation options, and scarce environmental awareness compared with Richmond’s college neighborhoods, particularly around the VCU campus. She also pointed out how “marginalized people would find this area exclusive because there are a lot of Blue Lives Matters flags and people not wearing masks. I can’t imagine people of color would feel safe walking here.” I found this exercise beneficial to my students even beyond the pandemic since they could turn “the ethnographic lens inward to their own families, homes, and neighborhoods” (Stephano 2020), practicing the kind of student-centered learning that we strive for in the college writing class (Pryor and Bowman 2016, 444).

Writing: Creating Material Culture Texts

Once students have practiced analyzing material culture texts and ethnographic observation, they are ready to produce their own material culture texts. While the bulk of student writing in my courses involves a research-based, argumentative paper, a focus on creating material culture texts earlier in the semester allows students to practice writing and argumentation using different media, while solidifying the notion of material culture.

Memorial Building Exercise. This assignment includes a hands-on memorial-building component, a documentation component (photo), and a reflective writing component in the form of a photo essay.11 In preparation, I introduce the notion of grassroots memorials by illustrating examples, starting with local ones such as the memorials set up at Marcus-David Peters Circle (formerly known as Lee Monument) next to the Lee statue in the summer of 2020.12 Once students familiarize themselves with the idea of memorials, they start building their own memorial display and showcase it somewhere in their apartment, house, garden, or a public place of their choice. One potential issue to consider is that this assignment might be too triggering for some students; I find the last two questions in Section 4 of the assignment important because they offer students an opportunity to share and reflect on potential triggers.13

Memorial Building Exercise. This assignment includes a hands-on memorial-building component, a documentation component (photo), and a reflective writing component in the form of a photo essay.11 In preparation, I introduce the notion of grassroots memorials by illustrating examples, starting with local ones such as the memorials set up at Marcus-David Peters Circle (formerly known as Lee Monument) next to the Lee statue in the summer of 2020.12 Once students familiarize themselves with the idea of memorials, they start building their own memorial display and showcase it somewhere in their apartment, house, garden, or a public place of their choice. One potential issue to consider is that this assignment might be too triggering for some students; I find the last two questions in Section 4 of the assignment important because they offer students an opportunity to share and reflect on potential triggers.13

Given the particularly difficult circumstances of the pandemic, I believe that this project has the potential to help students not only cement the notion of material culture and learn about the cultural and social narratives embedded in local material objects, but also find a mindful moment in their everyday lives. For example, one student in my Food for Thought course put together an elaborate memorial display in memory of her Ajja or paternal grandfather, who passed away five years ago and was her “closest link to [her] Konkani heritage.” Reflecting on the assignment, the student writes how she “learned that [she] still feels a great sense of loss for [her] Ajja, and through a conversation with [her] mum, that [they] share a lot more traits than what [she] remembered.” She also “found the symbolism of each object and dish to be the most interesting because it allowed [her] to think about memories [she doesn’t] usually recall” and she “learned how food, rituals, and memorials are a really important aspect of [her] family, and are significantly tied with [her] memories, experiences, values, and heritage.” Moreover, the exercise encourages students to reflect on emotional events in their lives through the combination of reflective writing and a hands-on activity as healing from pandemic, protest, and school-related stress, including Zoom fatigue. In her reflective essay, another student writes how she “learned that memorials can make you pause from life for a minute and take a time to be thankful and think about something that maybe you don’t want to think about in order to show them or yourself that they meant something to your life.”

Decolonizing the Classroom

Students choose a material culture topic for final essays through brainstorming, library research, and scaffolding exercises.14 Reflections on their research journey throughout the semester reveal their urge to write about what they know—especially in the midst of the pandemic and BLM protests—and remind me of my commitment to enable my students to speak out against social and racial injustice in Richmond and beyond. Writing about African American hairstyles, one student points out how “[g]rowing up as a Black girl with type 4 hair, [she] was always conflicted over [her] hair and whether it was beautiful. [She] would often hear kids refer to type 4 hair as ugly, unmanageable, and nappy. Up until the age of 17, [she] rarely wore [her] natural hair out of fear of being judged and persecuted. Eventually [she] began to embrace [her] hair and love [her]self. However, in the year 2021 as an adult, jobs and institutions are telling [her] the exact same things that [she] used to hear when [she] was growing up.” In her research proposal, another student explains how she chose to write about museums because “[i]n Richmond, Virginia, there are historical sites that portray Indigenous people and people of color’s known history.” “For a long time,” the student continues, “I imagined museums as a way of showcasing information but never realized the effect they had on Indigenous people and people of color until I wondered how museums obtained these objects.” After researching this topic throughout the semester, the student decided to “examine the responses that museums have taken to outline the consumption and misrepresentation of Native artifacts” to “showcas[e] how to culturally appreciate a culture instead of culturally appropriating one.” The personal and rhetorical growth that students achieve by writing about the material cultural objects around them is evident in the way that this student’s intentions progressed from initial proposal to final paper. These examples show the kind of social and cultural self-awareness that as a folklorist and a teacher I aspire to see more and more in the writing classroom. This reminds us how folklore can equip educators with tools and resources to engage diverse students and audiences more fully in the process of making and appreciating creative texts.

Incoronata (Nadia) Inserra is an assistant professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, where she teaches interdisciplinary writing courses as part of the core curriculum. She received a PhD in English from the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa with focus on Folklore and Cultural Studies. Her research interests include folklore as community engagement, community-engaged pedagogy, and place studies. She is the author of Global Tarantella: Reinventing Southern Italian Folk Music and Dances (Illinois Press, 2017).

Endnotes

1 VCU is one of 54 universities designated as community-engaged by the Carnegie Foundation (VCU Office of the Provost); the VCU Division of Community Engagement currently supports development of service-learning courses across the curriculum and a variety of community-engaged research projects, while VCU’s strategic plan for 2018-2025 features “collective urban and regional transformation” among its main themes (VCU Inclusive Excellence).

2 The Department offers several courses designated as service-learning, while helping organize and actively participating in the VCU Common Book Program (VCU’s version of the nationally recognized Summer Reading Program) as well as engaging in a shared learner-centered curriculum focused on diversity, equity, and inclusivity. In particular, our 2018-20 course theme—space and place—provided a great opportunity for me to share community-engaged resources with my colleagues and students and research and teach material culture topics. As a member of the Richmond as Text Faculty Learning Community, I have also been able to consolidate my community-engaged approach by sharing and discussing Richmond-related resources and relevant pedagogical material with fellow community members.

3 Both Richmond’s Confederate history and its current rewriting within the BLM Movement are embedded in the city landscape and evident to any observer who would take even a short walk along Monument Avenue and search for the (mostly) still-standing Confederate statues or read street names (both old and renamed ones). Beyond this history, Richmond’s white supremacist legacy is evident from how the city is currently divided into neighborhoods, which in turn correspond to historically segregated white and Black neighborhoods and are also the result of decades of racist housing policies (Campbell). This sharp division is still evident today in the uneven distribution of healthy food options (Vaughan), public transportation (Jordan), and green space in the city (Plumer and Pokovich), while many see a direct continuity between Richmond’s history and the current process of gentrification (Williams). More importantly, VCU administration has been criticized for being directly involved in this process of gentrification by contributing to rising housing prices and therefore to the forced relocation of historically marginalized communities (Smith).

4 Such texts include, but are not limited to, Richmond’s monuments (both Confederate and more recent ones representing African American heroes), enslaved trails, neglected African American cemeteries that are now being restored (Palmer), a growing (and often politically charged) mural collection, as well as various museum collections and exhibits, whose expansion has been spurred, among other things, by VCU’s renowned art program.

5 As a writing instructor, I also find that material culture analysis helps students practice close-ended questions, which students will then use for their research topic brainstorming and library search activities and review the difference between open and closed questions as they put together their own research questions.

6 This exercise was inspired by a material culture analysis workshop held by my colleague Elizabeth Fagan, who specializes in history and archeology (Fagan), as well as by fellow folklorist Lee Timreck’s class visit and lecture on “Visualizing Emancipation: An Artistic Narrative of the African American Emancipation Experience” (Timreck).

7 Students’ quotes in this section are from my UNIV 200 Inquiry and the Craft of Argument course in Fall 2020.

8 I am grateful to folklorist and material culture scholar Laura Ruberto for sharing Littman’s article. One caveat is that some students might be unable to conduct the walk physically; that is something I share with them at the beginning of the course to give myself time to devise an alternative assignment for those students who need it.

9 Students’ quotes in this section are from my UNIV 200 course in Spring 2021.

10 As one student notes, “While the cobblestone path [in Richmond] is a fun and interesting feature while walking, it is frankly just annoying while you’re driving. Also you can’t stop to enjoy the natural beauty or architectural beauty while driving. I really get to pull in the details and connect to the area around me while walking. While driving I’m just trying to get somewhere.”

11 Here I focus on the memorial building and photo documentation component. Students are also invited to share the project in class as a PowerPoint/Google Slide presentation or record a VoiceThread presentation.

12 In my food class, we also discuss several food-centered memorial traditions from around the world, including the Mexican ofrenda tradition as well as the Southern Italian tradition of St. Joseph’s Table, to offer a variety of examples and models.

13 I let students know that they have the choice to come up with an alternative assignment together with me (although I usually provide an option from the get-go). Another way is to let students pre-record a VoiceThread presentation, which works as a good alternative for those who feel too triggered to share this assignment live to the class and more generally for those students who tend to be shyer about presenting in class. Another problem I encountered is that students have a lot of freedom in building their own memorial and, as a result, their displays range from very complex to very simplistic. I tried to solve this issue by adding strict building requirements, but students’ feedback showed me that keeping the memorial design flexible is important to let students enjoy the process. In the future, I plan to leave students free to explore the memorial design as they see fit, while also asking them to elaborate on their final products in more detail in their photo essay.

14 I leave students free to choose among a variety of material culture objects that they are able to observe on or off campus—not only monuments, statues, and murals, but also African American hair braiding, ethnic fashion, or tattoos, for example.

Works Cited

Badger, Andrew. 1975. Folklore: A Source for Composition. College Composition and Communication. 26.3:285–88.

Bowman, Paddy. 2004. “Oh, that’s just folklore”: Valuing the Ordinary as an Extraordinary Teaching Tool. Language Arts. 81.5:385-95.

—. 2006. Standing at the Crossroads of Folklore and Education. Journal of American Folklore. 119.471:66–79.

Bowman, Paddy and Lisa Rathje. 2017. Introduction. Journal of Folklore and Education. 4:5-6. accessed June 1, 2021, https://www.locallearningnetwork.org/journal-of-folklore-and-education/current-and-past-issues/jfe-vol-4-2017/introduction-2017.

Campbell, Benjamin. 2012. Richmond’s Unhealed History. Richmond: Brandylane Publishers.

Curtis, Jennifer O. 2014. Captivating Culture and Composition: Life Writing, Storytelling, Folklore, and Heritage Literacy Connections to First-Year Composition. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. Accessed June 1, 2021, https://www.proquest.com/docview/1640916514?pq-origsite=primo.

Department of Focused Inquiry. About Us and Mission Statement. Accessed June 1, 2021, https://focusedinquiry.vcu.edu/our-department.

Fagan, Elizabeth. 2019. Visual and Material Culture Analysis. Focused Inquiry Symposium at Virginia Commonwealth University. November.

Jordan, Rachel M. 2019. Transit Access Equity in Richmond, VA. Masters of Urban and Regional Planning Thesis. Richmond: Virginia Commonwealth University.

Littman, William. 2020. Viewpoint: Walk this Way. Reconsidering Walking for the Study of Cultural Landscapes. Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum. 27.1:3-16.

Liu, Rossina Zamora and Bonnie Stone Sunstein. 2016. Writing as Alchemy: Turning Objects into Stories, Stories into Objects. Journal of Folklore and Education. 3:60-76. Accessed July 12, 2021, https://www.locallearningnetwork.org/journal-of-folklore-and-education/current-and-past-issues/journal-of-folklore-and-education-volume-3-2016/writing-as-alchemy-turning-objects-into-stories-stories-into-objects.

Local Learning. 2019. More than the Right Questions: A Workshop on Interviewing for Learning and Engagement. American Folklore Society Annual Meeting. October.

Naming the Lost. Accessed June 1, 2021, https://namingthelost.com.

Palmer, Brian. 2017. For the Forgotten African-American Dead. New York Times, January 7. Accessed June 1, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/07/opinion/sunday/for-the-forgotten-african-american-dead.html.

Plumer, Brad and Nadja Popovich. 2020. How Decades of Racist Housing Policy Left Neighborhoods Sweltering. New York Times, August 24. Accessed July 12, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/08/24/climate/racism-redlining-cities-global-warming.html.

Pryor, Anne and Paddy Bowman. 2016. Folklore and Education: A Short History of a Long Endeavor. Journal of American Folklore. 129.514:436-58.

Rendleman, Julia. 2020. Reuters, June 30. Accessed June 1, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/news/picture/photos-of-the-month-june-idUSRTS3FWZW.

Rogers Thomas, Kara. 2018. Rubbing Shoulders or Elbowing In: Lessons Learned from a Folklorist’s Contribution to Interdisciplinary Scholarship. Journal of Folklore and Education. 5:1:64-70, https://www.locallearningnetwork.org/journal-of-folklore-and-education/current-and-past-issues/jfe-vol-5-2018/journal-of-folklore-and-education-volume-5-issue-1/rubbing-shoulders-or-elbowing-in.

RVA Creates. Overview. Accessed June 1, 2021, http://rvacreates.com/overview.php.

Smith, Camryn. 2020. One VCU Master Plan: The Anatomy of Gentrification and VCU. Ink Magazine, April. Accessed June 1, 2021, https://www.inkmagazinevcu.com/one-vcu-master-plan-the-anatomy-of-gentrification-and-vcu.

Stefano, Michelle. 2020. On Remote Fieldwork and “Shifting Gears.” Folklife Today, May.

Timreck, Lee. 2019. Visualizing Emancipation: An Artistic Narrative of the African

American Emancipation Experience. Class lecture. Virginia Commonwealth University. February.

Virginia Commonwealth University Inclusive Excellence. About Us. Accessed June 2, 2021,

https://inclusive.vcu.edu/about.

Virginia Commonwealth University Office of the Provost. Facts and Figures. Accessed June 2, 2021, https://irds.vcu.edu/facts-and-figures.

Living in a Food Desert. 2015. Virginia State University Documentary. Directed by Jesse Vaughan. Jesse Vaughan and Cedric Owens producers, Petersburg, VA. Accessed July 12, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jicYbi-8ZNU.

Williams, Michael Paul. 2017. We Remain Two Richmonds. Richmond Times Dispatch, July 24. Accessed June 1, 2021, https://richmond.com/news/local/williams-we-remain-two-richmonds—rva-blossomed-while-richmond-is-being-left-further/article_2c9d466f-c300-55fd-9ddb-7ba85bef339b.html.